Towards vs Away Moves: Getting Clear on What Truly Matters to YOU

Overview

This article is essentially about how we can live a life that has more meaning and purpose, and how we can become the best version of ourselves. We can only achieve these things by getting clearer on who we truly want to be, and by increasing our awareness of (and by choosing to do) what is most important.

Not only do we need to become clearer of what is most important to us (i.e., clarifying our values, their meaning, and why these things truly matter to us), we also need to develop and draw upon problem-solving and emotion regulation skills that will help support us when challenges and setbacks arise.

We begin by discussing how ‘meaning’ and ‘purpose’ (which relate strongly to our values) are essential for guiding us through life’s challenges. Following this, a simple framework (Towards & Away Moves) is presented to help us increase our self-awareness, to assess our options, and to make more workable decisions, particularly in the face of life’s challenges.

Man’s Search for Meaning

Viktor Frankl was an Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist who during WW2 was separated from his wife and children and was imprisoned in a Nazi death camp. As a way of protecting himself psychologically from the barbaric and dehumanizing traumas forced upon him, he used his training to document objectively the horrific experiences he witnessed and experienced (which he does in graphic detail in the book, “Man’s Search for Meaning” which has been translated to over 26 languages).

Through his observations, he stumbled across the incredible realisation that certain prisoners (who may not have been the most physically strong—including himself) were in connection with ‘something important’ that many others did not possess: They attached ‘meaning’ to their suffering and therefore had a deeper ‘reason’ to keep going.

He discovered that because of this ‘reason’ they could endure hardships with more resilience while many others appeared to give up (others often became sick and died or collapsed while working and were beaten to death).

For Viktor Frankl, he realised that this special ‘something’ was ‘HOPE’. He hoped to survive the experience of being reunited with his wife and children. He did whatever he could to keep his hope alive.

Each day, he gave meaning to his suffering by viewing every hardship, punishment, and beating as a ‘necessary’ next step to ultimately being reunited with his wife and children. Each night, while staring at the moon through the bars of his cell, he would savor and tend to his hope by imagining that his wife was also staring at the moon at that exact moment. In this way, he would cultivate feelings of warmth and connection with her.

Sadly, after the war was over and he was freed (spoiler alert), he discovered that his wife and children were murdered at their death camp several years prior. Importantly, as crushing as this was for him – he candidly shares his reflection that had he known this at the time it would have crushed his hope and he likely would not have had any reason to persist through the gruesome punishments thrust upon him as a prisoner in his Death Camp. This highlights how important it is to connect with greater meaning and purpose, no matter how difficult the challenges of your situation may feel.

Although it took him many attempts to write the book (earlier versions were seized and destroyed several times by Nazi Prison guards), Viktor Frankl wrote Man’s Search for Meaning as a memoir of his experiences, reflections and observations: Connecting with meaning can help us endure the most grueling situations and hardships. Through Meaning, we can connect to the ‘bigger picture’; a reason ‘why’ we would want to persist when life is difficult. In this way, ‘meaning’ helps focus on what we want, which organises our brains and behaviour in potent ways that direct us to what we need to do to overcome our current challenge.

Viktor Frankl’s experience shows that even when we have no choice ‘leave’ or ‘change’ a situation, we can change how we respond to that situation. His gift is the lived-experience that connecting to a greater purpose can allow us to endure even the most challenging situations and experiences.

Man’s Search for Meaning is a short book that has 2 sections: Part 1 (about 40 pages) contains the incredible observations Viktor Frankl made of himself and others about how MEANING connects us with a POWERFUL REASON to persist in the face of absolute adversity. To be truly resilient in the face of life’s challenges, being able to connect with our deeper ‘values’ around what is most important to us and who we genuinely want to be (despite all of our life’s challenges) is a HUGE protective factor. Therefore, Part 1 of this book should be on everyone’s bucket list.

Important Themes:

- Meaning is essential to psychological well-being

- Find meaning in your suffering

- We do not pursue happiness; rather, happiness results as a side-effect of discovering ‘reasons’ to be happy

- Meaning is the motivating force in any person’s life

- Life asks us the meaning of life (it’s our choice); we do not ask life

- No matter what happens, no one can take away the meaning we give something

Important Frankl quotes to contemplate:

“Those who have a ‘why’ to live, can bear with almost any ‘how’.”

“Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

“Ever more people today have the means to live, but no meaning to live for.”

Two Choices We All Have: Towards & Away Moves

Many people are stuck in a pattern where they make the same choices repeatedly, even though this is not helping them move forward in important areas of their lives. Why do you think this might be?

Although there are specific reasons for getting stuck repeating specific interpersonal patterns (which I have written about here) often we all can also become stuck repeating unworkable patterns when we are in a mode of ‘autopilot’. This happens when we are not fully mindful of a) what is most important to us in a specific situation, and b) just how much the interaction between our thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations are affecting our perceived choices and our resulting behaviours. (Essentially, this requires Values-Clarification – discussed later – and Mindfulness.) As a result, we can become very reactive to the situation and can act in ways that are not in line with the person we truly wish to be.

This is because when we are on ‘autopilot’ and face a challenging situation, we are extremely susceptible to reacting to whatever our minds, our emotions, and our physical sensations are telling us (vs connecting with the ‘bigger picture’ and acting based on that which is most important to us. I.e., our values; the person we ultimately wish to be; our best version of ourself given the difficulty at hand).

There are distinct brain-based explanations for why this can be so difficult (which I have written about here and here and here). However, for now, simply understand that powerful ancient brain-systems can often lead to us acting in ways that make things worse and are therefore ultimately unworkable.

When we are on autopilot, although we may feel ‘as though’ we do not have a choice (or ‘as though’ our actions happened ‘to’ us), we will often behave in ways that are unlike the version of ourselves that we truly wish to be (e.g., we may do or say something hurtful to people we care about – or we may avoid something meaningful because on face value it is ‘hard’, or we may self-sabotage – these would be examples of ‘Away Moves’ discussed below).

Yet, even though it might not feel like it – no matter how tired, how stressed, or how angry we are at any moment – we do actually have a choice over what we do. Although we may not control a situation, even within that situation we can choose how we behave in that situation (Remember the above quote from Viktor Frankl: “Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”). However, although simple to understand, this is not necessarily easy, and it requires awareness, skills, and practice!

With no awareness of what is most important to us (or when we are not clear on the person we truly want to be in a particular situation) often when the going gets tough we take actions aimed at reducing, escaping, or relieving negative emotions. This may work temporarily, but ultimately it makes the situation worse because: a) there is no way to eliminate any emotion permanently; and b) because now we are moving away from the person we truly want to be (or the life that we want to create) and this can make us feel trapped, guilty, or regretful, or that life lacks purpose and meaning.

For instance, without awareness of what’s truly important, when faced with a challenging situation, we can get easily become caught up in wrestling with distressing thoughts, images, memories, or predictions. We can experience strong negative emotions that can feel so uncomfortable that we become fixated on seeking ways to avoid them. This may lead some people to avoid or escape, or act on urges to lash out at Self or others. These are all away moves: Short-term actions that function to reduce distress that ultimately pull us away from the direction that is most important to us.

Eg, If we hold the value: ‘Being a loving partner’ (but we have had a long, tiring, and frustrating day), we might temporarily lose contact with our value. It is then that we are likely to will act to reduce the momentary discomfort we are feeling (fatigue and discomfort) which may mean withdrawing from, being unsupportive towards (or even attacking) our partner. Although we may have acted to ‘turn down the volume’ on our discomfort, our actions are essentially an ‘away move’ because they pulled us away from ‘being a loving partner’.

So, whenever we are unclear about (or lack awareness of) what is truly important to us, and whenever we have strong negative emotions or become side-tracked by our what our minds / emotions are doing, often we can get caught up in a struggle with trying to reduce, avoid, or eliminate these inner experiences. Without skills to deal with what’s going on inside of us, we are likely to act in ways that pull us away from acting like the person we truly wish to be, and this can make a situation worse for either ourselves or those around us.

Towards & Away Moves

In any situation, there are only two choices we can make:

Towards Moves:

Actions that bring us closer to the person we truly want to be. These are actions that bring us closer to the people and experiences that matter most to us.

Away Moves:

Actions that pull us off-course or further away from the person we truly want to be in a situation. Away Moves are actions that will often make a situation worse.

The Price of Admission to a Meaningful Life

In any situation, either we are ‘moving towards’ or we are ‘moving away’. It might not be that we want to move away from what is most important to us (or that we want to behave unlike the best version of ourselves). Rather, by acting in ways to reduce or avoid the distress or discomfort with challenging situations, emotions, or thoughts (which is understandable to want to do), we unfortunately simultaneously close off the Towards Move option. ‘towards moves’ (doing what truly matters) will often stir up challenging emotions, thoughts, urges, and feelings (e.g., feeling frustrated, fearful, or awkward). If we cannot be a container for these inner experiences, we will ultimately seek to turn the volume on them down, which also unfortunately means we cannot keep moving in the direction that matters the most to us.

Within any situation, either we are making a towards move or we are not. Either we are behaving as the best version of ourself, or we are not. Unfortunately, there is no way to not choose. If we do not want to choose (which is perfectly OK), we need to realize that by not choosing, often we are inadvertently choosing ‘away’ (until we choose ‘towards’).

Realize, however, that this is in constant flow and that it is not ‘black and white’. We all make away moves from time to time (and that’s OK). What is important is how we address this and what we do about it. Also, sometimes we may make what looks like an away move in one situation, so that we can make a towards move in some other situation that is more important to us.

For instance, putting an important decision off—if (say) because we are tired and need to think about it when feeling rested and clear-headed, or because we need more information to decide—isn’t necessarily an away move. But, getting fixated on ensuring certainty in decision-making, or getting fixated on making ‘the best’ choice if that holds us back and impedes us moving forward (or missing out) may be an away move.

But what about painful or threatening thoughts and/or complex feelings?

Away Moves in Anxiety

People experiencing strong anxiety invest enormous amounts of energy trying to not have anxious thoughts and feelings. Often this involves avoiding any thoughts or situations that may make their anxiety worse–eg, taking risks where one could fail, being in situations that involve uncertainty or situations that cause discomfort (like being assertive, being around people, or being intimate) … or getting stuck in thoughts about ‘what if‘…

Although this is understandable (because anxiety feels bad), the problem is that anxiety often generalizes. So (for instance) someone who may have had a car accident may avoid riding in cars. But this could then generalize to catching public transport. This anxiety could also generalize to ‘speed’, which may mean that riding a bicycle could cause high levels of anxiety (and would thus then need to be avoided). As you might imagine, this can happen easily and can cause a person to become stuck with a greater problem than the source of the original anxiety.

The effects from avoiding these experiences could be far-reaching: Fewer opportunities to socialize, to work, to engage in pleasurable activities. This could cause loneliness or depression and could even affect on our chances of meeting a life partner and creating a loving relationship. In other words, the long-term outcome of avoidance is that we may forego a meaningful life for the sake of comfort.

Although it may make sense to avoid things that make us feel anxious, if we build our life around avoidance the cost (to us) is that we will experience an ever-shrinking window of tolerance which will mean that what we ‘can’ do (according to our anxiety) will become smaller and smaller, until we are struggling to live a rich and meaningful life.

Given that anxiety can generalize – the list of potential triggers could grow and could be potentially endless! However, what people rarely realise is that what is being avoided is not the activities per se, but the thoughts or feelings that become triggered by those activities. The problem with using avoidance as a coping strategy for reducing anxiety is that our options become narrower and narrower. The more we avoid, the more things actually seem to trigger anxiety. Now we are doing less, but the anxiety remains. We may end up trapped in a self-created prison.

Away Moves in Depression

What about depression? It’s common–and normal–for people struggling with feelings of low mood to report agitation, fatigue, low energy, self-criticism, and a reduction in pleasure for practically everything. Depression can be terrible! And it understandably also robs us of our motivation.

Yet, a common trap people experiencing low mood fall into is one of ‘affective forecasting’ – incorrectly predicting that something in the future will not be good because we do not feel good right now (eg, “I feel down therefore I can’t go anywhere or do anything because I won’t enjoy it” or “I just don’t feel like it”).

This leads to us to miss out on having new experiences while doing nothing to improve our mood. Worse, we may feel worse because nothing has changed, we may even feel guilty or ashamed about not showing up, or we may feel angry at ourselves for missing out on yet another opportunity to do something different. This can lead to feeling depressed about being depressed.

However, even when having a really difficult time, it is still possible to connect with what is truly important and to take small actions in that direction – even if you are having negative thoughts or feelings or are struggling with feelings of low motivation (and we all will at some stage).

Goals & Towards Moves

Emotions vs Behaviours

Often people turn to their emotions (or ‘feelings’) as a measure of how capable they are (or are not) able to take action (e.g., “I don’t feel like I can” or “I feel awkward, therefore I can’t”). This is a trap.

Unlike behaviour, which is something we can choose to either do or not do, the problem with valuing an emotion – or making it a goal – is that an emotion is not something we can choose to ‘do’. (To prove this – think about how successful you have ever been eliminating all unwanted emotions from your life, forever…?).

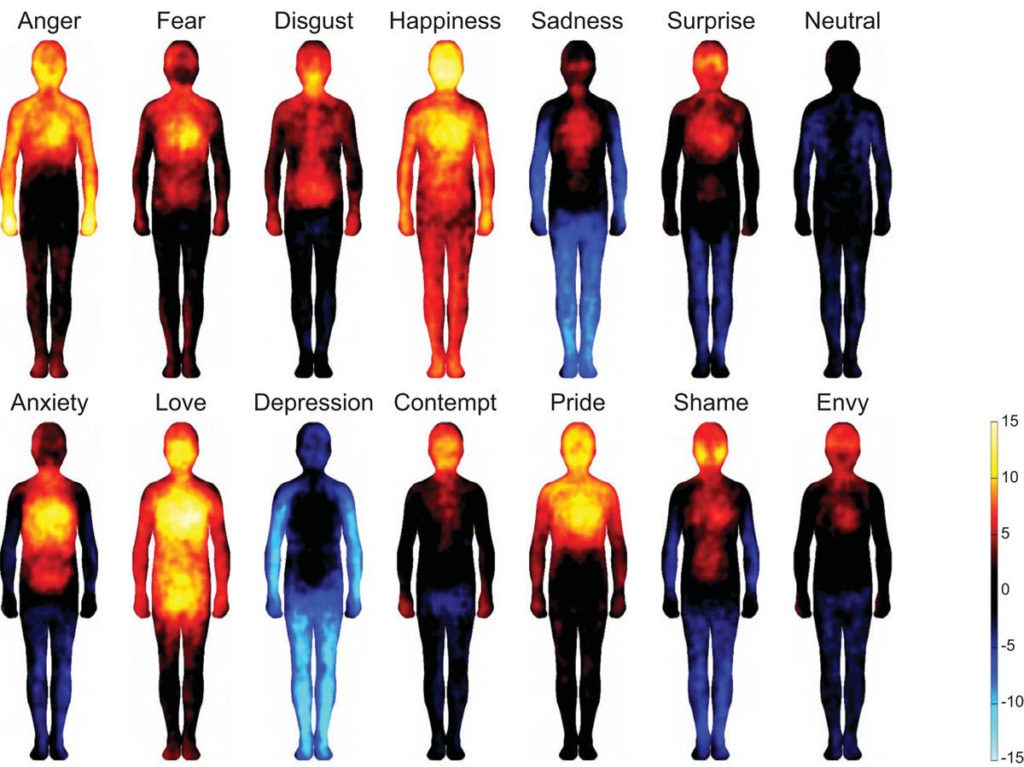

An emotion cannot ’cause’ us to do something – it is simply an experience that we feel in our mind and bodies. As pictured below, we know different emotions can activate a distinct set of body parts:

The above image is from a study of 701 people who were asked to show the body locations where they feel basic emotions (top row) and more complex ones (bottom row). Warm colours (Red-Yellow) represent regions that people commonly report are stimulated when they experience a particular emotion. Cooler colours (i.e., Blue-White) indicate areas of deactivation. Neutral (no emotion) is represented by the absence of colour (i.e., Black).

It may seem obvious, but feelings are not actions (i.e., emotions are not behaviour). Emotions feel powerful because they can create urges that appear to motivate us to act (or to avoid). This is especially true whenever are not being skillful in handling powerful emotions. The following is true of us all: When we are outside of our own window of tolerance, we will have fewer choices in how we respond.

One problem with relying on our emotions like a ‘compass’ is that feelings are transient (and often unpredictable) experiences that are highly influenced by momentary internal and external factors (e.g., ever been so hungry you become angry, or ‘hangry’? Or have you ever been so sleep-deprived that you became highly frustrated or overwhelmed ?).

Using our emotions like a ‘compass’ for what we can (or cannot) do can also become a trap because it may lead to us to connect with how much (or little) we feel like doing something – or it may lead us to want to avoid feeling our feelings (which is common across most mental health difficulties).

Second, although ‘good feelings’ feel ‘good’, they are not necessarily helpful to embrace as our ‘purpose’ for several reasons. Although most of us prefer pleasure over pain, we have very little choice over which feeling we are going to experience moment-to-moment. In fact, we have dozens of emotions each day (many of which happen as a reaction to our situation). Yet, we are more likely to respond to threats, challenges and setbacks with threat-based emotions and internal experiences of discomfort or aversion (because this is how our brains are wired). Thus, it could be said that “choosing to tolerate discomfort” while on our path is more likely to result in success, because discomfort is inevitable ‘sometimes’ AND because we do not get to choose how we feel.

Although we have little choice over our emotions, we do have choice over our actions (which include how we respond to our emotions). When we connect with what is most meaningful to us, we are empowered with the option to either take actions that will bring us towards (closer to) or away (further from) the outcome we most deeply desire.

Although most of us are averse to discomfort (we prefer pleasure over pain), when we become willing to tolerate discomfort as we move towards a chosen path, we can open ourselves up to being able to feel any emotion in the pursuit of a desired outcome. This is an empowering position to take regarding our emotions because even though we cannot stop negative emotions, they ultimately will have less influence.

Key points so far:

- Emotions are the result of a complex psychological and physiological interplay that may (but not always) have motivational and/or survival value

- Emotions can ‘feel’ powerful in the movement and can influence our choices if we act on them, but ultimately emotions are are not causal

- Emotions are not the same as ‘actions’ (eg ‘anger’ is not the same as the action of slapping someone in the face).

- Although we do not get to choose our emotions, we can learn to choose how we respond.

- Choosing to “tolerate discomfort” while on our path is more likely to result in success, because discomfort is inevitable, ‘sometimes’.

Working with Behaviour: Focus on what you ‘do’ (NOT feel)

It is possible to work towards cultivating more positive feelings. It is also possible to increase our capacity to handle challenging emotions AND to develop more helpful responses to ourselves during such times (eg, by engaging in Self-Care behaviours such as Self-Compassion practices). In this way we will increase our overall Window of Tolerance to handling all kinds of stress. However, we can not eliminate all negative emotions as all emotional experiences are hardwired into our architecture and emotions (positive and negative) can have useful guiding functions (when they are in proportion).

People often forget this when they define ‘happiness’ as “freedom from negative emotions”. Often, people pursue this (emotional) idea of happiness as a way of life. Eg, “I will be happy when I no longer feel …”. Yet, this approach comes at a cost (because avoiding negative emotions is impossible).

Making “freedom from negative emotions” a life goal will easily frustrate us, because it is an impossible goal to achieve. Thus, we will essentially be constantly failing and we know that failure triggers negative emotions such as threat (!).

A more helpful approach would be to: a) decide on a meaningful direction; to b) determine that actions that will take us towards this direction in behavioural terms (remember: a behaviour is not an emotion, it is something we can do or can choose to not do); to c) determine what emotions we may need to tolerate (and what skills we could use to help ourselves with this process); while d) remembering that emotions (good and bad) are part of life because they are inside us (i.e., ‘everywhere we go, we take the weather’).

It is important to keep in mind that we have dozens of emotions each day and we do not have any choice over what feeling we are going to experience next. Taking actions based on our values is bigger than how we may feel moment-to-moment. Think back to the book ‘Man’s Search for Meaning’ by Viktor Frankl who focused on Meaning not emotions (clearly he would have had mostly negative emotions every day). Focusing on moving towards meaning (Towards moves) vs. trying to get away from negative emotions allowed him to persist in getting through his difficult situation.

Powerful emotions can cloud our judgment. This is not our fault (it is how the human brain evolved), but it is our responsibility to manage. When flooded by powerful emotions, may find it very difficult to act in ways that we normally might. For example, when experiencing significant emotional distress, it can be tempting to do things that are unhelpful (e.g., we may become angry at at ourselves or others). These are away moves.

Yet, during these times, by simply realising that we are experiencing a difficulty and reminding ourselves that we want to help ourselves can be helpful. Although we might not expect ‘big things’ from ourselves when we are struggling, even something as small as ‘Self-Care’ would be helpful (vs harmful). And this may be all that we can do. (This is still a Towards Move because we have not made things worse).

Again, some people view discomfort as the price of admission to living a meaningful life. In this way, learning how to be more comfortable with discomfort is a way forward (learning how to help yourself through tough times is a towards move)!

In this way, Self-care is an example of a towards move. There are multiple pages on this website that offer information and tools we can use to engage in Self Care (links are at the bottom of this page). One of the simplest ways we can engage in self-care is to attend to and engage in soothing breathing.

Although it may not ‘feel’ like we are achieving all that much, by simply being with ourselves because discomfort is difficult, we are ultimately not making it worse. Even though we may feel terrible, by not making things worse, we are essentially helping to make them better (and we know that no matter how small, the benefits of small consistent efforts add up, as pictured below).

Values in Relationships

A fantastic practical example of what being clear on your values can look like in in the context of healthy (mutually Attachment secure) adult relationships is clearly evident in the (now) infamous “A Credo for My Relationships With Others“ by Clinical Psychologist Dr. Thomas Gordon. While you are always free to choose your own values, as you read through this Credo, I invite you to reflect upon whether you are achieving something like this within your important primary relationships (and if you are, reflect inwards about whether your are achieving this same harmony and respect internally – between the competing internal aspects of your Self):

A CREDO FOR MY RELATIONSHIPS WITH OTHERS

You and I are in a relationship which I value and want to keep. Yet each of us is a separate person with our own unique values and needs and the right to meet those needs.

So that we will better know and understand what each of us values and needs, let us always be open and honest in our communication.

When you are having problems meeting your needs, I will listen with genuine acceptance and understanding so as to facilitate your finding your own solutions instead of depending on mine. And I want you to be a listener for me when I need to find solutions to my problems.

At those times when your behavior interferes with what I must do to get my own needs met, I will tell you openly and honestly how your behavior affects me, trusting that you respect my needs and feelings enough to try to change the behavior that is unacceptable to me. Also, when some behavior of mine is unacceptable to you, I hope you will tell me openly and honestly so I can try to change my behavior.

And when we experience conflicts in our relationship, let us agree to resolve each conflict without either of us resorting to the use of power to win at the expense of the other’s losing. I respect your needs, but I also must respect my own. So let us always strive to search for a solution that will be acceptable to both of us. Your needs will be met, and so will mine—neither will lose, both will win.

In this way, you can continue to develop as a person through satisfying your needs, and so can I. Thus, ours can be a healthy relationship in which both of us can strive to become what we are capable of being. And we can continue to relate to each other with mutual respect, love and peace.

Dr. Thomas Gordon, 1978

Why S.M.A.R.T goals are ‘DUMB’

While we are talking about ‘towards moves’, it is important to discuss goal setting. You may have heard of ‘SMART Goals’ (?) – If not, ‘S.M.A.R.T’ is basically an acronym that is commonly promoted as ‘the holy grail’ for guiding goal setting. Although there are variations on the acronym, S.M.A.R.T Goals refers to the concept that in order to be ‘effective’ we (‘should’) always select goals that are:

-

Specific

-

Measurable

-

Achievable

-

Realistic

-

Time-related

Although the SMART goals framework can be useful for goal setting in the workplace, it could be argued that when we constantly pursue goals that are not tied to our deeper values (i.e., actions that resonate with our own personal meaning and purpose), our lives will ultimately feel lacking in some way.

This is because without a connection to deeper meaning or purpose (i.e., the things that you truly value), pursuing goals that do not truly matter can make the benefits of achieving them seem redundant. Signals that this is happening may include: Life is feels repetitive, bland, shallow, robotic, or meaningless. We may also lack motivation and/or we may feel like ‘giving up’ when difficulties inevitably arise.

We know that Depression and many other mental health difficulties share a common side effect of being disconnected from meaning (in fact, for Depression, often a lack of meaning can be a major contributing factor in low mood and existential dilemmas). Similarly, burnout can result from the relentless pursuit of achievement that can often become disconnected from deeper meaning (e.g., rigid rule-following behaviours such as completing long lists of tasks that rarely have much meaning for the sake of crossing them off a list vs pursuing a life filled with balance, connection, and Self-Care). So, SMART Goals that are not aligned with your deeper values are ‘dumb’.

Before setting SMART Goals: Clarify what is most important to you (your values – what truly matters). Sometimes, this may begin with identifying what you don’t want. That’s OK (!) – This may be necessary to help you clarify the ‘WHY?’ – Why you would ever want to persist with a particular action ? (this step is very important for when challenges and difficulties arise, because they will, because life can be challenging).

Once you know ‘WHY’, then identify the ‘WHAT’: What will you need be willing to tolerate as you pursue the goal? (e.g., frustration, impatience, setbacks, failure). You can THEN plan how you might respond to each of these difficulties. Remember: Goals that are not chosen with these factors in mind are often either abandoned when the going gets tough, or become aversive and draining of valuable motivation and energy for living (yes—even SMART GOALS).

Once you know all these things, you may wish to make use of the ‘SMART goals’ acronym. However, remember this: Pursuing goals that are not important to you is unlikely to be a source of deep fulfilment, irrespective of whether you use the SMART Framework. Connect with meaning by clarifying your values, and link your goals to that deeper purpose (then apply the SMART framework!).

“Those who have a ‘why’ … can bear with almost any ‘how’.”

Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning

Towards Moves: How To?

First, we need awareness. This is not always an easy. This means having an awareness of our thoughts—which includes not only thoughts but beliefs, the ‘stories’ our minds tell us, threatening images, painful memories, and our mind’s unhelpful predictions.

It also means having an awareness of our needs and our emotions– which includes ‘needs’ for comfort, safety, connection, love and acceptance; and difficult emotions such as fear, anger, pain, and sadness. Finally, it requires an awareness of difficult physical sensations – such as tension, physical stress, or discomfort, and urges to reduce this tension/discomfort by reacting in unhelpful ways that are the opposite to how we truly want to act.

Mindfulness can help us develop this awareness. Mindfulness means observing—our inner experiences and the world around us non-judgementally—that is, without reacting with evaluations (eg ‘this is good’ or ‘this is bad’). Mindfulness also helps to develop self-compassion and compassion for others, which can be tricky for certain people. Mindfulness can also help us develop an awareness of how our thoughts and emotions can feed off each other and become amplified like a negative feedback loop. When this happens, it can seem like we have no choice.

In order to make more Towards Moves, we also need to get clearer on what we want in terms of the ‘bigger picture’. This means getting clear on what is truly important—figuring out what matters to you the most in terms of people you care about and the person you truly want to be. This is deeply personal – it is about what you value most (not what society tells us to value); that which is most meaningful to you.

You also need an awareness of how you are making away moves. It can help to talk about this with someone who you trust – someone with whom you feel safe and respected. It can also help to work with a Clinical Psychologist that knows how to do values-clarification. Not all psychologists know how to do this. A practitioner who is trained in delivering Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (pronounced ‘ACT’ as in taking action) is someone who can guide you through this process. You can read more about ACT here.

Finally, in order to make more ‘towards moves’, we also need to develop skills in dealing with difficult thoughts, emotions, physical urges and sensations. These are bound to ‘show up’ as we step into the unknown and move towards the things that we deeply care about. Often, these ‘skills’ are very specific – they are not things we can read about on a screen or a page. These skills are best learned in therapy, because therapy can guide us to attend to areas that we cannot see clearly for ourselves.

Help Me Choose

Naturally, we can learn mindfulness and get clearer about what we value most – including becoming more aware of the person we truly want to be (our values) and increasing our awareness of the ‘away moves’ that keep holding us back. We can read books and websites to develop skills with dealing with the difficult thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations that are likely to arise as we move towards what’s truly important. You can do this on your own, but it is much easier to do this with help.

Because “discomfort is the price of admission to living a meaningful life”, and because discomfort is inevitably going to arise whenever you take steps towards something that is deeply important to you, learning about how to handle discomfort is essential. A Clinical Psychologist trained in Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT) can present these things in a way that makes sense and is tailored to your own unique situation.

A clinical psychologist trained in ACT can present these things to you in a way that is tailored to your own unique situation and history. They can also help you get clearer on why you are get stuck and react the way that you do. They can help you determine what is truly important (to you). They can teach you mindfulness skills, and they can help you become skilled in developing ways of responding differently to difficult thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations (eg, urges) so that you can meet the demands of the situation in ways that are truly workable in terms of your needs and the person you truly want to be. This includes helping you clarify what is most important to you (values clarification), and helping you to develop new ways of responding to the mind and its inner dialogue, including: thoughts, beliefs, ‘stories’ we tell ourselves, images, memories, predictions; strong difficult feelings – emotions such as fear, anger, pain, sadness; and difficult physical sensations – urges. The good news is that these are all skills that can be learned.

If you want help to clarify your values so that you can make more towards moves and become the best version of yourself that you can be, then let’s talk. I can help you to get clear on what you value, and can help you create a life rich with meaning and purpose. I can also help you identify and break unworkable patterns by teaching you new ways of responding to negative thoughts, uncomfortable feelings, and strong physical sensations (such as tension or urges to avoid or react).

Knowing these things will allow you to respond to demands of challenging situations in improved ways that are workable in terms of your needs, the people you care about the most, and the version of yourself that you ultimately want to be.

Further Resources

- Learn about common difficulties in learning Mindfulness

- Understand your Window of Tolerance

- Deal with negative thinking

- Your Brain’s 3 Emotion Regulation Systems

- Dealing with your inner-critic

- Discover the Fears, Blocks, & Resistances to Self-Compassion

- How your Attachment Style influences your emotion regulation and your relationships

- View a list of all articles that I have written