Overview:

Attachment is an evolutionary framework that explains how humans form and maintain relationships across their lifespan. Attachment is one of the most extensively researched areas in psychology, with over 60 years of studies in humans and decades of earlier work in animals (including Lorenz’s 1930s observations of imprinting in newborn ducklings and Harlow’s 1950s experiments on the effects of maternal deprivation in primates).

Our attachment style develops in response to the emotional quality of care provided by our primary caregivers. Early attachment experiences profoundly shape key aspects of human development, including how the brain and immune systems grow, how we learn to self-regulate during challenging situations, and how we experience and communicate emotions and needs. These early experiences continue to influence us as adults, shaping how we understand relationships, the partners we choose, and even the degree to which we seek emotional connection or distance from others.

This page explores how attachment styles develop and how they affect day-to-day functioning. Early attachment experiences shape our inner world and significantly impact both our relationships with others and with ourselves. Understanding these dynamics is essential, as they can profoundly affect our well-being and personal growth.

When early caregiving is marked by neglect, inconsistency, or a lack of love—whether real or perceived—it can lead to long-term mental health challenges and limit overall potential and happiness. This is because attachment patterns also extend to how we treat ourselves. They influence our ability to notice personal suffering and respond to emotional needs—or, in some cases, explain why we’ve learned to ignore those needs altogether. Our responsiveness to ourselves, or lack thereof, is often shaped by what we were (or were not) taught by our early caregivers. Recognizing and addressing these attachment wounds can be a vital step toward healing and developing a more compassionate relationship with ourselves.

For many, the following saying rings true: “We spend the first 15 years learning how to survive life with our family, and the rest of our lives healing from it.” Clearly, this is a profoundly important topic that deserves careful attention, reflection, and care. Understanding how our attachment experiences have shaped us is essential, as is considering the process of healing past attachment wounds.

What is Attachment?

Our earliest attachments with parents or caregivers shape our abilities and expectations for relationships throughout life. The quality of these early bonds influences how our brain and immune system develop, how we form a sense of self, and whether we learn (or struggle to learn) how to regulate our emotions. These foundational relationships also shape how we pursue closeness or independence, what we believe about how relationships work, and what we expect from our partners.

Attachment styles help explain how people respond differently to challenges such as:

- Uncertainty or distress

- Strong emotions (both positive and negative)

- Setbacks (and how we cope with failure)

- Understanding and communicating emotions (our own and the emotions of others)

- Making bids for emotional intimacy

- Eliciting care from others and responding to that care

- Expressing expectations within a relationship

- Identifying and communicating needs (both ours and our partner’s)

- Handling conflict and emotional disconnection

A person’s attachment style forms in childhood and serves as a blueprint for navigating life and relationships in adulthood.

How Attachment Develops

Attachment processes begin even before birth. Prenatal experiences significantly shape early emotional bonds and the development of stress regulation systems in infants. Research indicates that fetuses can respond to their mother’s emotional states, exhibiting increased movement during positive emotions and soothing touch and reduced movements during negative emotions (links to these studies here and here). These early interactions not only foster attachment but also lay the groundwork for emotional regulation and relationship patterns later in life.

From birth, because we rely entirely on caregivers for basic needs such as food, shelter, and affection, our brains have evolved to prioritize connection (whilst being highly attuned to the threat of disconnection) in order to ensure our survival. Thus as infants, we are highly attuned to how others respond to us and how our actions impact those around us.

Early attachment experiences play a critical role in shaping brain and immune system development, with decades of research demonstrating that the quality of our earliest attachments with caregivers can trigger a cascade of genetic, cognitive, social, and physical changes, contributing to lifelong outcomes in either positive or negative ways.

The ‘Still Face’ Experiment

The infamous ‘still face’ experiment (developed by Dr Ed Tronick in the 1970’s) is a powerful demonstration of a child’s need for connection and how vulnerable we essentially all are to the emotional or non-emotional reactions of our primary caregivers. This experiment gives us insight into what it is like when connection does not occur.

Non-emotional reactions are a signal of ‘disconnection’, which triggers a range of instinctual behaviours in an infant. The ‘still face experiment’ illustrates the effects of perceived ’emotional disconnection’ and demonstrates how vulnerable we all are to emotional connection (and disconnection) from our primary caregivers, be they male or female.

Although the ‘still face’ may seem like a trivial example, as you may be able to appreciate, as a child develops there are many complex factors at play between them and their caregiver that will continue to shape and to ultimately teach a child about emotion regulation and self-soothing, how to connect emotionally, and how to elicit care (including a child’s experience and expectations of care as being ‘available and helpful’).

Father-infant responsiveness

While the mother-infant bond is often emphasized, the quality of a father’s bond and emotional responsiveness is also critical to a child’s development. Fathers play a unique and vital role in shaping a child’s emotional landscape, attachment patterns, and long-term well-being.

Research shows that infants engage in the same connection-seeking behaviors with their fathers as they do with their mothers, as demonstrated in the following video. Infants respond just as strongly to a father’s ‘still face,’ illustrating how essential the father’s emotional presence is to the child’s sense of safety and connection.

These connection-seeking behaviors reflect an innate survival mechanism, deeply shaped by early parent-child interactions. The responsiveness (or lack thereof) from caregivers during these early years plays a formative role in determining how, when, and why we seek—or avoid—connection in adulthood. It influences our ability to trust others, form close relationships, and regulate emotions, laying the foundation for interpersonal dynamics throughout life.

The following video captures what it is like for babies of parents who are immersed in their phones. Notice how absorption in a device triggers exactly the same response in a child as the parental complete non-responsiveness in the previous videos:

The Four Attachment Styles

Four attachment styles have been identified, born out of the seminal work of psychologists John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. In the 1950s, Bowlby proposed that attachment is the product of evolutionary processes and that infants are thus born with an innate drive to form attachments with caregivers. In the 1970s, Ainsworth developed a paradigm (the ‘Strange Situation’) to determine attachment security in children within the context of caregiver relationships. The ‘Strange Situation’ procedure involves series of eight interactions lasting approximately 3 minutes each, whereby a mother, child and stranger are introduced, separated and reunited. From this research, Ainsworth identified three main attachment styles (a fourth attachment style was later identified in the 1980s by psychologists Main and Solomon).

The four attachment styles consist of Secure Attachment and three Non-Secure Attachment Styles listed and described in detail with examples, below:

1) Secure

2) Anxious (aka Preoccupied)

3) Avoidant (aka Dismissive)

4) Disorganized

Secure Attachment:

Secure attachment is the ideal attachment style. Approximately 50-60% of adults have a Secure attachment style. A Secure attachment between a child and a caregiver forms when the caregiver is perceived as safe, predictable, consistent, and physically and emotionally available. The remainder of people develop one of three other attachment styles (Anxious, Avoidant or Disorganized, as discussed in the next section).

Secure attachments develop in the following ways: A securely attached infant believes her parent is safe, available, and responsive when she is in distress. Caregivers communicate these qualities the following ways: Facial expression, posture and tempo of body movement, tone of voice, physical proximity and tactile responsiveness, which together communicate a dependable, caring intention from the caregiver. (This is all pre-verbal information that an infant is constantly learning about and absorbing.) When a secure bond has been established, even the mere attention from or presence of a caregiver can help the infant to regulate distress.

As a result of a secure bond, even if the parent is not always available, the infant will learn to internalize these responses from their caregivers and they can draw on this internal representation to self-soothe and self-regulate during challenges or times of distress. As you can begin to see, this is essentially the origin of where we learn (or sadly where we fail to learn) emotional regulation.

Children with a secure attachment see their parent as a secure base from which they can venture out and independently explore the world. When a caregiver is emotionally responsive and strives to meet an infant’s emotional needs with consistency, the infant is taught to be emotionally responsive themselves. Thus, securely attached children grow into resilient, emotionally healthy adults who enjoy emotionally healthy relationships because they generally feel trusting and safe in those relationships.

In intimate relationships, a secure adult feels secure in their connection with their partner (even in their partner’s absence). This allows each partner to live their lives freely (which is called interdependence). Because a Secure individual is aware of and is able to respond in emotionally healthy ways to their own needs, this frees them up to be supportive at times when their partner feels distressed. Also, because a secure adult feels comfortable eliciting care from others, they are more likely to turn toward (vs shutting down or withdrawing from) their partner when they feel troubled.

In other words, an intimate relationship with a secure partner tends to be honest, open and equal, with both parties feeling independent, yet loving toward each other. Because of this, it is unsurprising that we find that compared to the other attachment styles, securely attached adults (and their partners) report feeling the highest levels of relationship satisfaction.

People with a secure attachment style:

- Generally feel close to others and maintain positive, healthy relationships.

- Feel comfortable with both emotional and physical intimacy, as well as with maintaining independence and personal space.

- Communicate effectively and are adept at resolving conflicts as they arise, using open and honest dialogue.

- Have fairly stable relationships, marked by mutual respect, trust, and understanding.

- Generally trust their partner and believe in the reliability and consistency of their relationship.

- Feel safe being vulnerable with their partner, sharing their thoughts, feelings, and needs without fear of judgment or rejection.

- Exhibit a balanced approach to relationship dynamics, valuing both closeness and autonomy.

- Are usually confident in expressing their emotions and can handle stress and challenges within the relationship constructively.

- Maintain a healthy sense of self-worth and do not overly rely on their partner for validation or emotional support.

- Tend to have a positive view of relationships and believe in their ability to overcome difficulties together.

An Example of Secure Attachment

A fantastic example of what Secure Attachment ‘looks like’ in the context of healthy (mutually secure) adult relationships is clearly evident in the (now) infamous “A Credo for My Relationships With Others“ by Clinical Psychologist Dr. Thomas Gordon. As you read through this Credo, I invite you to reflect upon whether you are achieving something like this within your important primary relationships (and if you are, reflect inwards about whether your are achieving this same harmony and respect internally – between the competing aspects of yourself):

“A CREDO FOR MY RELATIONSHIPS WITH OTHERS”

You and I are in a relationship which I value and want to keep. Yet each of us is a separate person with our own unique values and needs and the right to meet those needs.

So that we will better know and understand what each of us values and needs, let us always be open and honest in our communication.

When you are having problems meeting your needs, I will listen with genuine acceptance and understanding so as to facilitate your finding your own solutions instead of depending on mine. And I want you to be a listener for me when I need to find solutions to my problems.

At those times when your behavior interferes with what I must do to get my own needs met, I will tell you openly and honestly how your behavior affects me, trusting that you respect my needs and feelings enough to try to change the behavior that is unacceptable to me. Also, when some behavior of mine is unacceptable to you, I hope you will tell me openly and honestly so I can try to change my behavior.

And when we experience conflicts in our relationship, let us agree to resolve each conflict without either of us resorting to the use of power to win at the expense of the other’s losing. I respect your needs, but I also must respect my own. So let us always strive to search for a solution that will be acceptable to both of us. Your needs will be met, and so will mine—neither will lose, both will win.

In this way, you can continue to develop as a person through satisfying your needs, and so can I. Thus, ours can be a healthy relationship in which both of us can strive to become what we are capable of being. And we can continue to relate to each other with mutual respect, love and peace.

Dr. Thomas Gordon (1978)

Non-Secure Attachment Styles

Below are descriptions of Anxious, Avoidant, and Disorganized Attachment Styles, along with the difficulties individuals may face. It’s important to understand that professional help can be valuable in addressing these challenges. Therapy can assist individuals in understanding their attachment patterns, developing healthier ways to express their needs, and improving their ability to form secure and balanced relationships. Through therapy, individuals can achieve personal growth and enhance overall life satisfaction.

Anxious Attachment (aka Preoccupied):

Children who had parents who at times responded well to their needs, yet at other times, were not emotionally present or may have responded in hurtful or critical ways, grow up feeling insecure, uncertain of what treatment to expect.

In relationships, adults with an anxious attachment style find that they need a lot of reassurance and responsiveness. Unlike a securely attached person, those with an anxious attachment style may appear overly dependent on their relationships to feel okay. Certain interactions or events may trigger deep mistrust and they may regularly feel heightened anxiety about the stability of their relationships.

Even though anxiously attached individuals may feel desperate or insecure, more often than not, their behaviour exacerbates their own fears (via a feedback loop called a ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’). They may also interpret independent actions by their partner as affirmation of their fears. Worse, when they feel unsure of their partner’s feelings or feel insecure in their relationship, they may become clingy, demanding or possessive toward their partner.

Although these are simply attempts to protect the Self via seeking a sense of safety, reassurance and security, by clinging to their partner or by engaging in behaviours called ‘Protest Behaviours’ a person with an anxious attachment style may unwittingly push their partner away. For example, if (say) a partner starts socializing more with friends, they may think, “See? He doesn’t really love me. I was right not to trust him – Maybe there is someone else… This means he is going to leave me.” This may lead to (for instance) lots of reassurance seeking behaviours, such as calling, texting, or even stalking or reading a partner’s private messages. Alternatively, it may lead to hostility towards that partner, who often will not understand the context of the person’s behaviour, and this may drive them away – particularly if the partner has an avoidant attachment style (below).

People with an anxious attachment style:

- Feel the need for lots of reassurance in a relationship.

- Often report feeling overwhelmed or extremely anxious when they and a loved one disagree or argue.

- Question their partner’s love, especially during times when their partner is away or not immediately responsive.

- Feel threatened by their partner needing a break and may pursue them persistently until they receive the reassurance they seek.

- May have a heightened sensitivity to perceived signs of rejection or abandonment, leading to intense emotional reactions.

- Frequently worry about their partner’s commitment and may engage in behaviors to test or seek confirmation of their partner’s loyalty.

- May experience difficulty with emotional regulation and rely heavily on their partner to manage their emotional state.

- Often fear being alone and may struggle with feelings of inadequacy or unworthiness in the relationship.

- Can become preoccupied with the relationship and may prioritize it over other aspects of their life, such as personal interests or friendships.

Individuals with an anxious attachment style may experience significant emotional instability, relationship difficulties, and a pervasive fear of abandonment. Their need for constant reassurance can lead to clinginess, conflicts, and low self-esteem, which negatively impacts overall life satisfaction. Therapy can be crucial in addressing these issues by helping individuals understand their attachment patterns, develop healthier coping strategies, improve communication skills, and enhance self-esteem. Engaging with a mental health professional can support personal growth and foster more secure and fulfilling relationships.

Avoidant Attachment (aka Dismissive):

Caregivers that were emotionally unavailable, absent, or unaware of their child’s emotional needs often raise children who develop an Avoidant attachment style. Perhaps crying was discouraged, or perhaps you were belittled for having emotional needs (vs being responded to with care, interest and warmth). As an adult, you may often feel uncomfortable with who you are or not know what you feel, and you may feel averse to situations in which you need to depend on someone, or be depended on by others.

A person with an avoidant attachment style lives in an ambivalent state, in which they are afraid of being both too close to and too distant from others. In relationships, they have fears of being abandoned but also struggle with being intimate. They may cling to their partner when they feel rejected, then feel trapped (or resentful, as though they will lose their sense of ‘Self’) if they become too emotionally intimate / close.

Often, in relationships, the avoidant style is attracted to the anxious style, and this sets off a push-pull between one partner (the anxious style) feeling unloved and the other partner (the avoidant style) feeling unable to meet the emotional demands of the other.

People with an avoidant attachment style:

- Tend to value independence over emotional closeness and may rely excessively on themselves for emotional soothing or support (e.g., ‘Compulsive Self-Reliance’).

- May suppress (numb), downplay, or struggle to share their deeper feelings with others.

- May experience difficulty forming deep, meaningful relationships (e.g. due to a mild sense of ‘mistrust’).

- Often feel awkward (or a strong urge to pull away) when a partner is seeking connection or is distressed.

- Regularly feel emotionally removed from or separate from others (which can result in experiences of defectiveness or alienation).

- May experience a strong desire to distance themselves from (rather than resolve) stressful situations or conflicts.

- Are generally uncomfortable with identifying, feeling, or expressing their deeper emotions (they may be cut off in their awareness of their bodies and/or may be numb to what they truly feel).

- May prefer fleeting, casual relationships to long-term intimate ones or may seek out partners who are equally independent (or who will maintain emotional distance).

- Are often accused by their partners of being distant and closed off, rigid, and intolerant. In return, they may accuse their partners of being ‘too needy.’

If you have an Avoidant Attachment Style, it is important to respect and learn to communicate your needs for space in a relationship in ways that reassure your partner that both they and the relationship are safe. Effectively communicating these needs helps maintain healthy boundaries while providing reassurance.

To do this, first identify what you need and consider how you can reassure your partner. For example, you might say:

- “This is not a reflection of how I feel about you—this is something that I need.”

Here’s an example of how to express your need for space using clear, empathetic, and reassuring language. This approach acknowledges your own needs while also being mindful of your partner’s feelings:

- “I’m sorry, but I’m not feeling very communicative right now. Please understand that my need for space at the moment—like not texting or engaging as much—is not a reflection of how I feel about you. Would it be alright if I take some time for myself right now? I promise we’ll spend quality time together later.”

By framing your need for space clearly and warmly, you can help your partner understand that it’s about your personal needs rather than a response to them or the relationship. This approach fosters open communication and mutual understanding, which supports a healthier dynamic. Developing various ways to express your feelings and needs effectively reassures your partner, helping them feel secure in the relationship. When your partner feels this sense of security, they are more likely to respect your need for space. This mutual understanding allows you to enjoy freedom and security in the relationship, strengthening your connection without feeling the need to withdraw to ‘survive.’ In this way, both partners can maintain a balanced and fulfilling relationship.

Disorganized (unresolved) Attachment:

Disorganized attachment is a primary attachment style commonly observed in survivors of complex developmental trauma (cPTSD). This can occur when a caregiver is frightening, abusive, or behaves in highly inappropriate ways, or when a child’s fundamental needs and rights are violated. Such traumatic experiences can instill a deep sense of fear and confusion in a child, who is inherently dependent on their caregivers for nurturance, safety, shelter, and sustenance. This dependency creates an internal conflict: while the child needs their caregiver for basic needs, they may also perceive the caregiver as a source of threat or betrayal. This conflict can lead a child to believe that the abusive behavior is their own fault or that they should remain loyal due to the caregiver’s role as a parent.

As an adult, individuals with a disorganized attachment style may yearn for closeness but simultaneously fear it. They might avoid seeking out relationships because they perceive reliance on others as unsafe. When faced with opportunities for intimacy, they may experience an internal struggle and pull away, reflecting the deep-seated fears and confusion rooted in their early experiences.

The consequences of disorganized attachment can significantly impact life satisfaction. Individuals may struggle with chronic emotional instability, difficulties in forming and maintaining stable relationships, and a pervasive sense of mistrust or insecurity. These issues can lead to feelings of isolation, low self-esteem, and dissatisfaction with personal and professional aspects of life.

People with a disorganized attachment style:

- May have had primary caregivers who were abusive (physically, emotionally, sexually, or through neglect).

- Commonly report craving emotional intimacy, but also feel it is safer to be alone, experiencing conflicting desires for connection and self-protection.

- May have had primary caregivers who alternated between showing love and being frightening or unpredictable, creating confusion about how to navigate relationships.

- May experience Complex Trauma (cPTSD) due to prolonged exposure to adverse experiences during formative years.

- Often have a deep mistrust of others, struggling to believe in the positive intentions of those around them.

- May exhibit inconsistent or erratic behaviors in relationships, reflecting their internal conflict and confusion about attachment.

- Often feel ambivalent about closeness, both yearning for and fearing emotional connection due to past trauma.

- May experience difficulties with emotional regulation and find it challenging to maintain stable, trusting relationships.

- May display a pattern of chaotic or tumultuous relationships, mirroring the unpredictability and instability experienced in childhood.

- Can struggle with a sense of identity and self-worth, frequently questioning their value in relationships and feeling uncertain about how to meet their own emotional needs.

A Word of Caution !

Before using attachment theory to blame or shame yourself—or your partner—for relationship challenges, it’s important to recognize the following: attachment styles are adaptive behaviors developed during childhood in response to our environment. While these patterns may no longer serve us in adulthood, they originally emerged as survival strategies. For example, a child who learns that relationships are untrustworthy or frightening naturally develops self-protective behaviors that carry into adulthood. These behaviors are not a flaw—they are understandable, adaptive responses to early experiences, rooted in the instinct to survive in a world where humans are born entirely dependent on caregivers for food, shelter, love, and safety.

However, while attachment behaviors are not our fault, it becomes our responsibility as adults to recognize how our early conditioning affects us. Healing involves understanding these patterns, acknowledging the ways they might limit or harm us now, and giving ourselves permission to make different choices. This process helps us replace old patterns with new ones that better serve us in our current relationships.

It’s also important to recognize that childhood attachment difficulties don’t only arise from extreme cases like abuse or neglect. Even well-meaning parents can unintentionally cause harm. Over-protectiveness, intrusive behavior, high expectations, or repeatedly dismissing a child’s feelings can all contribute to emotional distrust—of both relationships and one’s own emotions—well into adulthood. These experiences can result in insecure attachment styles, leading to anxious, avoidant, or disorganized behaviors. If you grew up learning that relationships were conditional, shaming, unstable, or rejecting, it is natural that you may struggle with uncertainty in relationships today. Again, these protective strategies are not your fault—they are natural responses to feeling unsafe or insecure during key stages of emotional development.

The key to liberation lies in understanding that these behaviors were protective strategies from an earlier part of life. They made sense ‘then’—but may no longer serve us ‘now’. That said, shaming or ridiculing ourselves—or our partners—for these attachment patterns is likely to perpetuate the same emotional wounds passed down through generations. This kind of blame only continues the cycle of intergenerational pain, rather than freeing us from it. True healing comes from compassion and understanding, both for ourselves and for others.

Attachment difficulties are not easily resolved with self-help tools alone, as attachment is inherently relational. It involves patterns of emotional learning and brain development that occur through interactions with others. Healing often requires working with a therapist who can offer an emotionally attuned, safe space for reflection, learning, and growth. A skilled therapeutic relationship can help you develop new emotional tools and practice healthy interpersonal behaviors—things that cannot be fully mastered in isolation. Seeking support is not a sign of failure, but a step toward breaking free from old patterns and building healthier, more secure connections.

In other words, healing attachment wounds requires more than self-awareness. Since attachment is relational, it takes safe, attuned relationships—like those found in therapy—to undo these patterns. Ideally, you want to seek new relational experiences that can provide the trust and security that you did not receive as a young person, to replace old coping strategies with healthier behaviors.

Attachment & Emotion Regulation

Emotion regulation is the process by which we influence how we experience and express our feelings (which emotions we have, when we have them, and how they are expressed). Throughout our lives, emotion regulation is an important regulator of interpersonal relationships and in our relationship with ourselves.

The ability to regulate one’s emotions is taught in one’s earliest relationships. We are taught ‘how’ to feel (and we are often not taught how to feel) by our primary caregivers, and this becomes ingrained throughout childhood, and practiced throughout life. Thus, emotion regulation and quality of an infant’s attachment are closely linked.

In infants, patterns of emotion regulation are shaped and developed in direct response to experiences with their caregivers. Because an infant is dependent on a caregiver (e.g., for food, shelter, and protection), an infant’s emotional regulation serves the important function for the infant of maintaining a close relationship with the attachment figure. This ensures that the parent will remain close to the child and the child will thereby (hopefully) be protected. As was demonstrated in the “Still Face” videos above – this is a survival instinct (we are hard-wired to do this).

Therefore, it is easy to understand how infants of non-secure parents, who may experience repeated rejection, or hostility, may learn very quickly to minimize their own negative affect (i.e., by emotionally withdrawing or shutting down) in order to avoid the risk of further rejection. Often, infants internalise the voices of their parents – and this can lead to an internalisation of this response to self that persists into adulthood in the form of negative self-beliefs and/or self-criticism.

On the other hand, it is easy to understand how infants of mothers who have been relatively inconsistently available may maximize negative their affect in order to increase the likelihood of gaining the attention of a frequently unavailable caregiver. If this strategy succeeds, it becomes engrained through repetition as a natural response whenever faces with a similar situation. Clearly, this could result in difficulties with emotion regulation for the child that may persist into teenage years and adulthood.

Again, both of these patterns of emotion regulation are simply examples of primal attempts by the infant to remain in positive connection with the caregiver. When these patterns work, they are repeated and they become deeply learned emotional responses – ways that we may still strive to have our emotional needs met as adults.

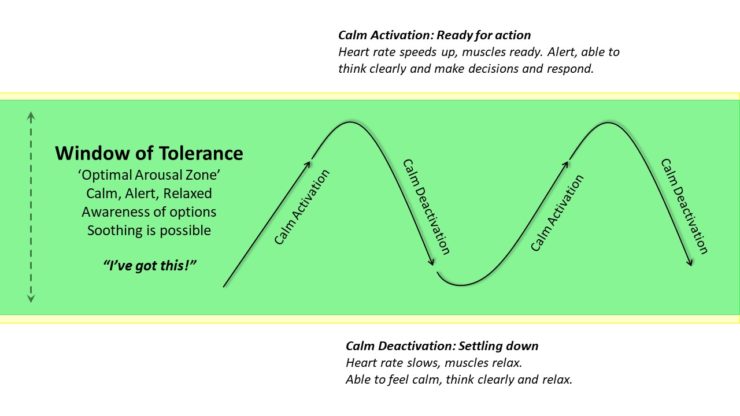

The early experiences you had with your primary caregivers ALSO play a direct role in the development of your brain, which in turn influences your ability to regulate your emotions. Insecure or inconsistent styles of attachment result in the experience of feeling overwhelmed and unsafe in a child, which creates either Hyperarousal (being on high alert) or Hypoarousal (becoming numb) as means of protection. Left unaddressed, this can persist across the lifespan and can greatly affect adult relationships, including our relationship with ourselves.

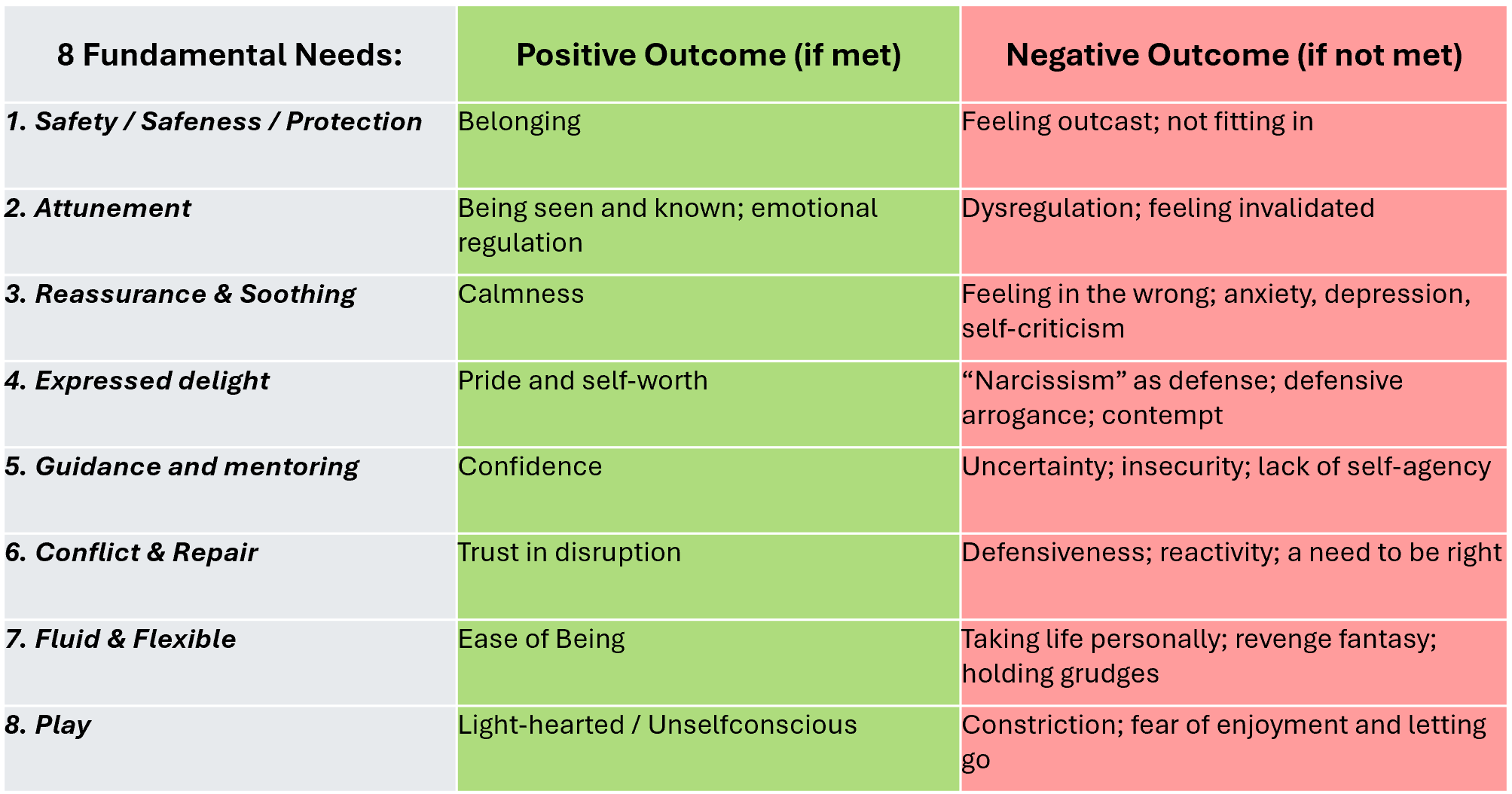

Over time, these learned protective behaviours can reorganise a child’s brain during a particularly crucial stage of development (0-15 years) and this, in conjunction with either adverse childhood experiences, skills deficits, or maladaptive coping strategies, can lead to difficulties with emotion regulation in adults (such as a reduced Window of Tolerance, discussed in detail here). Essentially this is because through interacting with an infant in a very critical period of brain development (especially between 0 to 12mths) the mother begins to teach and shape how to down-regulate negative emotions but ALSO how to up-regulate positive emotions (such as joy, interest, excitement, which are important for play-states and the development of the dopaminergic-reward system).

This is essentially what we as adults are ultimately required to do for ourselves, in terms of regulating our emotions (by calmly activating and deactivating our arousal) in response to the full range of events and challenges that we experience. This is depicted in a simple way in the following diagram (taken from my Window of Tolerance article, discussed in detail here):

Moreover, we know that the broader the range of emotions a child learns to experience (and respond to), the broader the range of emotions the adult will be able to understand, experience, and respond to (and understand, experience, and respond to in others).

For these reasons, it follows that, whereas skills for emotional regulation may come significantly easier to those who have grown up with secure attachment, emotional regulation can be more difficult to learn for those who grew up with inconsistent, unavailable or abusive caregiving. Nevertheless, the good news is that we can learn to work with (and heal) our wounded attachment systems, and regarding improving our emotion regulation – this essentially involves developing a new set of skills, which can be learned.

Effects on Relationships

In fact, this primary attachment style is so fundamental to how we process and make sense of the world that we even dream according to our primary attachment style. In one study, participants completed established measures of attachment to determine which attachment style best characterized them. Then, raters who were blind to the test results, listened to the participants’ recollections of dreams (listening carefully for themes, key people and the relationships between them). Amazingly, raters were able to correctly categorize participants’ attachment styles with a very high degree of accuracy, simply based on the content of their dreams (!). This result as been replicated in similar research.

In the area of intimate relationships, both male and female adults seeking long-term partners often identify qualities of responsiveness consistent with Secure Attachment caregiving (such as warmth, attentiveness, and sensitivity), as the “most attractive” qualities in potential partners. Yet, as you are probably aware, despite the attractiveness of these secure qualities, not all adults are paired with secure partners.

This is because it is common for people to find themselves in relationships with partners who confirm their existing attachment experiences regarding relationships, care, and love. In other words, as adults we are subconsciously drawn towards partners who replicate the attachment dynamics that we experienced as children – even when these dynamics are not helpful for us. (This is because our ancient brains are drawn to this ‘familiarity’ on a primal, subconscious level).

However, this need not be the case. If you are in a relationship that contains unhealthy attachment dynamics, you can become aware of them and work with your partner (or with a therapist) to improve and change unworkable patterns. Or, if the dynamic is truly dysfunctional and toxic, you can work towards terminating an unworkable relationship.

Alternatively, if you are not in an intimate relationship (or if you are not seeking one), understanding your Attachment style is still hugely important because it strongly influences how you relate to yourself and communicate with (and understand) others.

It’s Not Your Fault

As discussed earlier, there are many reasons a parent may struggle to be emotionally present with their children. For the most part, most parents try as best as they can to deal with the challenges of parenting with the emotional regulation skills that they have, many of which were passed onto them by their own parents.

Unfortunately, children of parents who lacked the capacity to understand how what they are doing was ultimately affecting their child’s psychological growth and well-being, will most likely be those who have the deepest attachment wounds (and challenges managing relationships, including their response to emotions and needs of the Self). This is because, as humans, we have built-in survival instincts. As infants, our attachment style was our best means of self-protection.

If you align with a “non-secure” attachment style, it is not because you did something wrong. Rather, your attachment style results from surviving your upbringing. In other words, a ‘non secure attachment style’ is a response to this period because it was how we learned to “balance out” the challenges of the caregiving provided to us. Any non-secure attachment style we may develop was the best way we to could cope with the difficulties of circumstances we were handed. In other words, our attachment experiences are not our fault (!). We did not choose our families, nor did we choose the difficult early childhood experiences we were exposed to.

No matter which attachment style you currently have, know that secure attachment is possible. Learning about attachment is a journey of healing, self-compassion, and moving towards a more secure attachment style that will ultimately lead to healthier, more rewarding relationships.

You can recover from your attachment wounds. You can learn to develop new ways to relate to yourself and to connect with others. Learning about attachment by reading this article (and some of the articles at the bottom of this page) marks the beginning of this journey…

Healing Your Attachment Wounds

We now know that the attachment style you developed as a child based on your relationship with a parent or early caregiver does not have to define your way of relating to yourself, or to those you love in your adult life. In fact, we know that healing our attachment wounds is possible through heathy, emotionally corrective relationships.

We know that healthy attachment to others is our primary protection against feelings of helplessness and meaninglessness. For instance, close, connected relationships can actually reduce anxiety and fear by easing our primal fear of abandonment. This is because strong, attached relationships reduce feelings of fear (threat activation) and help “calm the brain”.

Whereas emotional isolation is more dangerous for health than smoking or a lack of exercise (e.g., people who live alone experience three times as many strokes as those who are married), those who feel the safety of a comforting relationship actually are more resilient in life and can go out and take more risks. Quite simply, loving and being loved makes one stronger. Those who have trust in each other can turn to each other in times of distress and this creates even more emotional safety.

Emotionally corrective relationships can be intimate relationships that you may have with a trauma-aware emotionally supportive partner (or a close friend) who either has a secure attachment style or who has done a lot of this work in therapy themselves. This person may be willing to hold space for you while also holding you accountable, as you work through the pain of your past together in all the ways that this may emerge within the dynamics of your relationship. Again, these individuals are often people who have often already done the work of therapy and have done the work of breaking their attachment patterns. However, these relationships deserve to be cherished and they are not a complete substitute for working with a professional who is trained in helping people heal from attachment wounds.

Unfortunately, for people with complex attachment wounds, developing a secure relationship with the ‘right kind of person’ who is emotionally safe, knowledgeable, patient, unconditionally non-condemning and capable of providing a consistent secure base is a huge task, and there will likely be many hurdles along the way. Attachment patterns can be very challenging to understand and very resistant to change, and this can put significant strain on relationships. Again, working with a professional who is trained in helping people heal from attachment wounds is highly recommended.

Although self-help information can be useful, it is also important to seek help for attachment difficulties and not to rely on self-help material alone. This is because attachment is relational, it involves your brain’s development and emotional learning in the context of interactions with others. The learning, reflection, and healing that is needed to address issues of attachment require an emotionally-attuned and emotionally-safe therapeutic environment in which to do this work, and to practice interpersonal skills that cannot be mastered alone.

Developing Secure Attachment

Seen, Soothed, & Safe = Secure Attachment

Secure Attachment can be BEST summarized with the concept of: ‘Seen, Soothed, & Safe’. Although this idea was initially developed by Dr. Dan Sigel (Neuropsychiatrist, Researcher, and best-selling Author) to help simplify Attachment for parents seeking to understand, attune to, and provide for their child’s emotional and developmental needs, the concept of Seen, Soothed, & Safe can be applied to two further areas: How we as adults relate to others and more importantly, how we relate to (and care for) ourselves.

Seen

‘Seen’ means to acknowledge and understand the mind, and emotions of another. This involves showing interest, empathy and curiosity about the feelings, perspectives and needs of another and being supportive an responsive to the emotional worlds of another person (it is the opposite of a dismissive parenting style that ignores, invalidates, or belittles a child for having the feelings or reactions that they might be having). It also requires being able to remain ‘present’ with and attuned to another person. This is not simply about eye-contact; it is about any actions you can take that may communicate to another person that you ‘get it’ at a ‘feeling’ level – that you truly understand their emotional experience. Mindfulness skills, Active Listening skills, and checking that you have heard what someone is saying correctly, can greatly help with this.

Appling ‘Seen’ to Ourselves: This means developing awareness of our own internal worlds, being able to identify, understand, and take responsibility for working with our emotions. It also means identifying and understanding what we need, and being interested and willing to respond to meeting those needs. If this learning was not provided to us by our primary caregivers, this may require therapy and practice.

Soothed

‘Soothed’ means to provide a sense of comfort and calm to another when they are experiencing difficult emotions or situations, in order to help settle and soothe their nervous system, to provide emotional support, or to provide a ‘space’ to be with the difficulty that they may be experiencing. Soothing may be enhanced by the ways we use our voice (tone, speed, expression), and/or physical gestures like body language, eye-contact, hand holding, or hugging.

Applying ‘Soothed’ to Ourselves: Being able to comfort and care ourselves by responding to our needs with healthy self-care actions, that support, settle, and soothe our nervous systems are all hallmarks of being able to provide a sense of ‘soothed’ to ourselves when we are having difficulties. This may require the prior development and practice of self-regulation skills learned in either therapy or via useful self-help tools.

Safe

‘Safe’ means to provide a sense of emotional availability and/or protection to others which can be demonstrated in a variety of ways, such as via the aforementioned ‘Seen’ and ‘Soothed’ actions, by being ‘present’ and attuned to their inner worlds and demonstrating that you can be a stable and dependable figure during in times of distress. Other actions that cultivate a sense of ‘safe’ may include: Being able to provide emotional a ‘space’ for others where they feel accepted when experiencing their difficulty, by being reliably accountable for one’s actions where there is a contribution to the difficulty (i.e, taking appropriate responsibility to ‘right a wrong’), and checking-in on how another person is feeling in a reliable and a consistent way.

Applying ‘Safe’ to Ourselves: In addition to the skills required to feel we are ‘seen’ and can ‘soothe’ ourselves, being able to communicate through our intentions and our actions that we can care for ourselves in healthy ways (no matter what we may be feeling) can provide a deeper sense that we are ‘safe’ within ourselves. This is largely achieved by being able to respond to our inner worlds consistently with care, acceptance and compassion. This demonstrates to us that ‘it is OK’ to feel what we are feeling. Being proactively responsive to our emotions and our needs (which may include taking assertive actions to elicit care from others) and assertive communication skills are additional resources that can contribute to our sense of ‘safe’.

The video below summarizes the above concepts. Although it presents them as ‘4’ separate elements, they are essentially just 3 because: Seen + Safe + Soothed = Secure Attachment.

Individual Therapy

A skillful trauma-informed psychologist who has undertaken the appropriate training can offer you the experience of a healthy, emotionally corrective relationship. Such a therapeutic relationship has the potential to be an emotionally corrective relationship partly because it is the therapist’s job to be ethical, consistent, and to build in security while being fully present for their clients.

The goal of therapy in providing a secure attachment is to model healthy ways to relate to others and to provide a safe environment for you to learn to attend to and express your own feelings and needs, while also healing past wounds and practicing new skills. In this way, you can work towards developing more secure ways of relating to others, often referred to as ‘Earned Secure Attachment‘. With the support of your therapist, you will be able to begin to apply these new strengths outside therapy in relationships that matter to you such as with a partner, children and friends. This work can take time – but it can be done whether you are in an intimate relationship, or not.

In terms of using the emotionally corrective relationship of therapy to improve your relationship with yourself (which is also an important part of developing ‘earned secure attachment’), this may involve learning new ways of being able to soothe and support yourself when you are struggling or are experiencing a setback – these emotional skills will likely not have been made available to you as a child. For people with significant developmental traumas (such as attachment wounds or Adverse Childhood Events), therapies such as EMDR Therapy may be useful in helping you to remove the disturbance of painful memories so that you can put your past behind you, and create the relationships with yourself and others that you ultimately were unable to have.

If you are troubled by memories that disturb you, or if you are tired of being emotionally triggered by events, I recommend reading my page about EMDR Therapy.

Attachment-Focused Therapy for Couples (EFT)

The most well researched therapy for couples that makes use of attachment science is called Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) for Couples. EFT for Couples is a short-term therapy that is aims to improve attachment and bonding in adult relationships. EFT for Couples is about creating connection in close relationships. It helps couples to understand and express their emotional experience including their needs, feelings, thoughts, and behaviours.

EFT for Couples is acknowledged as the gold standard for empirically validated interventions in tested interventions for couples. This research shows large treatment effect sizes and impressively, stable results over time.

EFT is the only model of couple intervention that uses a systematic empirically validated model of adult bonding (attachment) as the basis for understanding and alleviating relationship problems. Developed over 30 years ago by Sue Johnson, EFT for Couples is essentially attachment science in a therapy. As has been discussed, attachment science views human beings as innately relational, social and wired for intimate bonding with others. The EFT model prioritizes emotions and emotional regulation as the key organizing agents in individual experiences and key relationship interactions.

Below is a short video explaining research that Sue Johnson and her team performed, involving brain scans of people in relationships who were treated with EFT for Couples. It demonstrates how developing a strong relationship bond can reduce feelings of fear (threat activation) and can help “soothe the threatened brain”.

EFT for Couples not only addresses factors such as relationship distress, intimacy, trust, and the forgiveness of injuries, but it also aims to influence and heal you and your partner’s attachment style.

Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) involves discussing specific incidents that may occur in your relationship, as a way to help each of you learn about your emotions and the behaviours that result from those incidents.

For example, your therapist may discuss your partner reminding you to take out the rubbish and how that makes you feel. Do you feel angry? What else might you feel? Are you ashamed because you forgot, so that makes you want to lash out in anger? Do you feel judged as “not good enough” by your partner and that makes you feel as if you disappointed her? Does this then make you want to pull away from her?

Goals of EFT for Couples:

- To create a positive shift in partners interactional positions and patterns.

- To foster the creation of a secure bond between partners.

- To expand and re-organize key emotional responses and, in the process, the organization of self.

If you are in a relationship in distress, or you would like to improve your relationship in any way, I highly recommend learning more about the work of Sue Johnson and finding a psychologist who can offer EFT for Couples.

For a summary of the research on EFT for Couples, please visit https://iceeft.com/eft-research/

Video explanation of EFT for Couples:

A more in-depth presentation about Attachment and EFT for Couples:

Parents & Caregivers

If you are a parent whose childhood attachment experiences were less than ideal, or worse, perhaps you were exposed to significant traumas commonly referred to adverse childhood events (ACEs), I recommend that you engage in therapy with a clinical psychologist that is trauma-informed, and attachment aware (Please note: Sadly, not all psychologists are). Options for family therapy also abound.

It is also be important to invest in education. My recommendations are to undertake one (or both) of the following established and researched-backed programs:

- Circle of Security (COS) training (external link):

An international program designed for parents and carers of children aged 0-12 years who want to strengthen the bonds with their children and would like support to help their children to build secure relationships. There is evidence that parents can in fact positively change a child’s insecure attachment style to ‘secure’ with COS training.

- Collaborative and Proactive Solutions (CPS) training (external link)

CPS is an evidenced-based model of psychosocial treatment developed by Dr. Ross Greene, and described in his books Raising Human Beings, Lost at School, & The Explosive Child (another highly recommended ground-breaking approach to understanding and parenting children who frequently exhibit severe fits of temper and other significantly challenging behaviours).

Rather than focusing on kids’ challenging behaviours (and modifying them), CPS helps kids and caregivers solve the problems that are causing those behaviours. This problem solving is collaborative (vs unilateral) and proactive (vs reactive). Research continues to find that that the model is effective at not only solving problems and improving behaviour but also at enhancing adaptive communication and emotion regulation skills.

- The Attachment Project (external link):

The Attachment Project is a (for profit) organisation that has useful Self-Help information for parents & caregivers (such as the specific link above) to help better understand how the different attachment styles develop in response to specific parenting strategies and styles. Their content is written by psychologists.

However, they offer an Attachment Style ‘quiz’ that is not a reputable diagnostic tool, nor is it empirically-validated (if you take this quiz, do so with ‘a grain of salt’). To their credit, the do state “The Attachment Project’s content and courses are for informational and educational purposes only. Our website and products are not intended to be a substitute for professional medical and/or psychological advice, diagnosis, or treatment.”

Summary:

- Attachment science explains how humans develop and function in relationships across the lifespan.

- Our ‘Attachment Style’ relates to the quality of our relationships with our primary caregivers.

- Our earliest attachments with parents or caregivers shape our abilities and expectations for relationships throughout life. The quality of our bond within these early relationships influences how our sense of Self develops, what we expect from our partners, and how we believe relationships work.

- Our early attachment experiences influence: How our brains developed; how we learned regulate our emotions in response to stress; and, how we relate to others and ourselves (including the partners we choose and how we believe relationships work, and we behave in relationships).

- Attachment styles are not our fault (or our choosing). Rather, they emerge early in our lives and are the result of previously ADAPTIVE, self-protective (i.e., ‘survival’) behaviours, that we developed in response to our upbringing. These patterns are often carried forward into adulthood, even though the resulting effects on our relationships with ourselves and others may be compromised or may become ultimately unworkable.

- Parents do not necessarily have to be highly abusive to have a negative effect on their children. Parents who are over-protective and intrusive, who are judgmental and have high expectations, or who are dismissive of a child’s thoughts and feelings can also cause a distrust of relationships – or even a distrust of a child’s own emotions – well into adulthood for that child.

- Attachment in conjunction with adverse childhood experiences and other developmental deficits (resulting in difficulties with emotion regulation or maladaptive coping strategies), can lead to difficulties with emotion regulation in adults (such as a reduced Window of Tolerance).

- Healing our attachment wounds is possible through a combination of learning, self-reflection, and heathy ’emotionally corrective relationships’ – this includes therapy with a trauma-informed, attachment aware therapist with whom you feel safe, understood and respected.

- Although self-help information can be useful, there is a need for safe guided reflection and learning of interpersonal skills that cannot be mastered alone.

- Because attachment is relational, we need an emotionally-attuned and emotionally-safe therapeutic environment in which to do this work. It involves working with our emotional understanding and responses in the context of interactions with others.

- Therapies such as EMDR Therapy may be useful in helping you to remove the disturbance of painful memories so that you can put your past behind you, and create the relationships with yourself and others that you ultimately were unable to have. Regardless of the therapy ‘type’, ensure you seek the help of a therapist who is trauma-informed, and attachment aware.

- Help for parents abounds in terms of individual and family therapy, and research-backed programs mentioned above in this article.

- Couples with attachment difficulties are recommended to invest in therapy with a therapist who is trained in Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) for Couples. Based on attachment science, EFT is the gold standard for couples therapy a therapy. EFT for Couples not only addresses factors such as relationship distress, intimacy, trust, and the forgiveness of injuries, but it also aims to influence and heal you and your partner’s attachment style.

- Understand that your attachment style may also affect how you engage in therapy. If you are receiving (or are planning to receive) therapy, I recommend reading the following article: How to get the most out of therapy.

Further Resources:

- How Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) impact on attachment, brain development and later lifestyle and health risk factors

- Your brain’s 3 Emotion Regulation Systems

- Getting Past Your Past with EMDR Therapy

- Emotion Regulation skills: Understanding your Window of Tolerance

- How to get the most out of therapy

- A list of all articles that I have written