Overview:

Attachment is an evolutionary model that explains how humans develop and function in relationships across the lifespan. Attachment science is one of the most researched areas in psychology. Its history spans over 60 years of research in humans alone, and many decades of research in animals prior (eg, from Lorenz’s observations of imprinting in newborn ducklings in the 1930s, to Harlow’s studies of the effects of maternal deprivation on infant primates in the 1950s).

Essentially, our ‘Attachment Style’ is formed in response to the emotional quality of the relationship provided to us by our primary caregivers. We know that early attachment experiences strongly influence human development in many key areas, including how our brains and immune systems develop, how we learn to self-regulate in response to both pleasant and unpleasant events, and how we learn to experience and communicate our emotions (and needs). As adults, our attachment experiences inform our perception and understanding of relationships and this heavily influences how we are likely to feel and behave in relationships, why we choose the partners we choose (and/or why we choose emotional distance from others).

This page aims to provide you with a deeper appreciation of how Attachment Styles develop and how they affect your current functioning. Early attachment experiences organize the internal worlds of us all and this influences the majority of our relationships (including our relationship with ourselves). Therefore, this a hugely important topic that deserves your time, attention, reflection and care.

Because neglect, parental inconsistency and a lack of love (experienced or perceived) can lead to long-term mental health problems as well as reductions in overall human potential and happiness, it is hugely important to learn about how our attachment experiences have shaped us, and for us to consider working towards healing our past attachment wounds. For many, there is truth to the anecdote: “We spend the first 15 years surviving living with our family and the rest of our lives healing from it”.

Not only do our attachment experiences shape how we are in relationships, they also extend to how we treat ourselves – this includes our ability to notice when we are suffering and also our response to our emotional needs (or why we may have learned to be insensitive to our emotional needs). This ‘responsiveness to Self’ (or a lack thereof such as when we are turning away from ourselves) is heavily influenced by what was (and often what was not – but should have been) taught to us by our primary attachment figures.

What is Attachment?

Our earliest attachments with parents or caregivers shape our abilities and expectations for relationships throughout life. The quality of our bond within these early relationships influences how our brain and immune system develops, how our sense of Self develops, and it also explains how we learned (or why did not learn) to regulate our emotions. The quality of our bond within these early attachment relationships also influences how we strive to satisfy our desire for closeness (vs independence), how we believe relationships work, and what we expect from our partners.

Attachment styles help explain how people respond differently when dealing with challenges of:

-

-

- Uncertainty or distress

- Strong emotions (negative and positive)

- General setbacks (and how we relate to failure)

- Understanding and communicating emotions (yours & the emotions of others)

- Making ‘bids for emotional intimacy

- Eliciting ‘care’ from others & responding to this care

- Communicating expectations within a relationship

- Identifying and communicating needs (your own and your partner’s)

- Conflict & emotional disconnection

-

So, a person’s attachment style first forms in childhood, and then serves as a model for navigating life and relationships in adulthood.

How Attachment Develops

Early in life, humans are predisposed to focus on learning about other people’s reactions and how our behaviour can affect others. As infants, we are completely dependent on our caregivers for food, shelter and affection. As a survival mechanism, our brains have evolved to be very focused on establishing connection, whilst being highly sensitive to disconnection.

The effects of our early attachments with parents or caregivers can trigger a cascade of changes genetically, cognitively, socially, and physically which can have either positive or negative lifelong consequences.

Unsurprisingly, early attachment experiences affect our relationship with ourselves (how we view and relate to ourselves during moments of difficulty) and our relationships with others (the partners we choose – or avoid – and the interpersonal patterns that we keep repeating with all others).

Essentially, this is because the same motivational systems that gave rise to the close emotional bond between parents and their children is responsible for the bond that develops between adults in emotionally intimate relationships.

Although our early attachment experiences do not necessarily have to define us, they set us up with a ‘template for relating’ to Self and Others, which ultimately becomes either an asset or risk factor in terms of our resilience to stress. We now know from decades of research that early attachment experiences heavily influence an adult’s susceptibility to mental health difficulties.

Still Face Experiment

The infamous ‘still face experiment’ (developed by Dr Ed Tronick in the 1970’s) is a powerful demonstration of a child’s need for connection and how vulnerable we essentially all are to the emotional or non-emotional reactions of our primary caregivers. This experiment gives us insight into what it is like when connection does not occur.

Non-emotional reactions are a signal of ‘disconnection’, which triggers a range of instinctual behaviours in an infant. The ‘still face experiment’ illustrates the effects of perceived ’emotional disconnection’ and demonstrates how vulnerable we all are to emotional connection (and disconnection) from our primary caregivers, be they male or female.

Although the ‘still face’ may seem like a trivial example, as you may be able to appreciate, as a child develops there are many complex factors at play between them and their caregiver that will continue to shape and to ultimately teach a child about emotion regulation and self-soothing, how to connect emotionally, and how to elicit care (including a child’s experience and expectations of care as being ‘available and helpful’).

Fathers are important too

Although the ‘mother-infant-bond’ is often cited as hugely important, we also know that the quality of a father’s bond and their emotional responsiveness is also hugely important to a developing child.

Notice how infants demonstrate the same connection-seeking behaviours to their fathers that the infants did with their mother in the previous video. Also, notice how these infants react just as strongly to their father’s ‘still’ face.

Again, understand that these connection-seeking behaviours and their associated reactions demonstrate an innate survival mechanism that is strongly influenced and shaped through parent-child interactions early in our lives. This ultimately informs how, when, why (and with whom) we seek (or avoid) connection as adults:

Although these are just very brief demonstrations, imagine the longer-term effects – over many years – of repeated parental unresponsiveness on the emotional development of an infant. Clearly, over time this would affect a child’s sense of safety and being their sense of feeling ‘cared-for’ by that parent. They may also go on to develop extremely negative views about themselves (such as ‘I do not matter’ or ‘I am unlovable’).

Unsurprisingly, research has shown that children who have parents who are not responsive to their needs have more trouble trusting others, relating to others, and regulating their own emotions.

Why do parents get it wrong?

Even for parents who want the best for their children, there are many reasons why they may struggle to be emotionally present in Secure Attachment ways with their children. For example, if you had a parent who was not responsive to your needs (was not Secure in their attachment style), or who may have even punished you for having certain emotions, you may struggle with knowing how to be Secure in your Attachment yourself. As a parent, you may have difficulties with emotion regulation or other emotional awareness ‘blind-spots’ that lead you to repeating behaviours similar to what you were exposed to with your own children.

At other times, parents lack the information about how attachment affects a child’s developing brain, or they may hold cultural (or outdated) beliefs about emotions and / or parenting that downplay the importance of maintaining an emotionally responsive connection with their children. Alternatively, some parents have strong dysfunctional beliefs about their own abilities (e.g., “I am a failure”) which can interfere with them being able to form a strong bond with their children. These are all common reasons why creating a Secure Attachment fails to occur.

On the other hand, there are also more complex challenges to developing Secure attachment. In households with children who are experiencing behavioural or other developmental difficulties, often parents become preoccupied with caring for that child to the detriment of the needs of other siblings. In households with divorce or a death of a parent there can be ruptures in the Attachment bond. In situations where there is domestic violence, it may be difficult (or unsafe) to show emotions. Unfortunately we know that people who were exposed to the following adverse childhood events (ACEs) can have difficulties with Attachment. Often these people had parents who were exposed to similar adverse events themselves (this is called intergenerational trauma).

We also know that drug and alcohol use can also negatively impact on emotional availability (and both intoxication and the resulting hangover can blunt emotional expression). Some parents have head injuries or other illnesses that make it difficult to show appropriate emotional reactions. Understandably, parents experiencing significant mental illnesses may also struggle to engage with their children in ways that cultivate a Secure Attachment bond.

However, there are also more common forms of disconnection that affect us all. Technology and ‘screen time’ has become a major part of our busy lives and nowadays it is not uncommon to see parents disconnecting from their children in the same ways that were demonstrated in the videos above, by simply using their phone.

For those who are interested, the following video captures what it is like for babies of parents who are immersed in their phones. Notice how absorption in a device triggers exactly the same response in a child as the parental complete non-responsiveness in the previous videos:

A Word of Caution !

Before you go down the road of using Attachment to blame or shame yourself (or your partner, if you are having relationship difficulties) please understand that: Attachment styles are ADAPTIVE behaviours from an earlier stage of life based on our upbringing. Although these behaviours may no longer serve us, they may be carried forward into adulthood. In other words, a child who is taught that relationships are untrustworthy or even frightening naturally learns to have SELF-PROTECTIVE behaviours in all of their relationships. This is not our fault – and it is completely understandable from a survival instinct perspective (after all, all humans are born completely dependent on their parents for food, shelter, nourishment, love and protection). However, as adults it is our responsibility to understand and heal from our childhood attachment conditioning, to help ourselves recognise that the past is affecting us and to provide ourselves with options (and the permission) to change and replace patterns that are no longer serving us.

Also, when considering your childhood attachment history, please keep in mind that parents do not necessarily have to be ‘highly abusive’ to have a negative effect on their children. Parents who are over-protective and intrusive, who are judgmental and have high expectations, or who are dismissive of a child’s thoughts and feelings can (over time) also cause a distrust of relationships – or even a distrust of a child’s own emotions – well into adulthood for that individual.

So in other words, if you learned in childhood that relationships are conditional, shaming, unstable, threatening, withdrawing or rejecting, it may cause you to be uncertain about relationships and this may lead to behaviours typical of the three non-secure attachment styles (anxious, avoidant, or disorganized behaviours). This is not your fault. These emotional reactions and their resulting protective behaviours are an understandable adaptive response to feeling insecure (or unsafe) in an important relationship during a critical stage of our development.

In other words, whereas being able to view attachment behaviours as ‘protective strategies from an earlier part of life that no longer serve us’ is crucial to our liberation, shaming or ridiculing ourselves (or our partner) for having attachment difficulties is probably doing nothing more than continuing to perpetuate the intergenerational toxicity that was handed down to us (or them) by caregivers. This is unlikely to result in freeing ourselves from these patterns and is more likely to continue to do further damage.

It is important to seek help for attachment difficulties. They are not easily resolved with self-help material alone. This is because attachment is relational, it involves your brain’s development and emotional learning in the context of interactions with others. There is learning, reflection, and healing that requires an emotionally-attuned and and emotionally-safe therapeutic environment, and there are skills that need to be honed and practiced interpersonally that cannot be mastered alone.

The Four Attachment Styles

The four attachment styles were born out of the seminal work of psychologists John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. In the 1950s, Bowlby proposed that attachment is the product of evolutionary processes and that infants are thus born with an innate drive to form attachments with caregivers. In the 1970s, Ainsworth developed a paradigm (the ‘Strange Situation’) to determine attachment security in children within the context of caregiver relationships. The ‘Strange Situation’ procedure involves series of eight interactions lasting approximately 3 minutes each, whereby a mother, child and stranger are introduced, separated and reunited. From this research, Ainsworth identified three main attachment styles (a fourth attachment style was later identified in the 1980s by psychologists Main and Solomon).

The four attachment styles consist of Secure Attachment and 3 Non-Secure Attachment Styles listed and described in detail with examples, below:

1) Secure

2) Anxious (aka Preoccupied)

3) Avoidant (aka Dismissive)

4) Disorganized

1. Secure Attachment:

Secure attachment is the ideal attachment style. Approximately 50-60% of adults have a Secure attachment style. A Secure attachment between a child and a caregiver forms when the caregiver is perceived as safe, predictable, consistent, and physically and emotionally available. The remainder of people develop one of three other attachment styles (Anxious, Avoidant or Disorganized, as discussed in the next section).

Secure attachments develop in the following ways: A securely attached infant believes her parent is safe, available, and responsive when she is in distress. Caregivers communicate these qualities the following ways: Facial expression, posture and tempo of body movement, tone of voice, physical proximity and tactile responsiveness, which together communicate a dependable, caring intention from the caregiver. (This is all pre-verbal information that an infant is constantly learning about and absorbing.) When a secure bond has been established, even the mere attention from or presence of a caregiver can help the infant to regulate distress.

As a result of a secure bond, even if the parent is not always available, the infant will learn to internalize these responses from their caregivers and they can draw on this internal representation to self-soothe and self-regulate during challenges or times of distress. As you can begin to see, this is essentially the origin of where we learn (or sadly where we fail to learn) emotional regulation.

Children with a secure attachment see their parent as a secure base from which they can venture out and independently explore the world. When a caregiver is emotionally responsive and strives to meet an infant’s emotional needs with consistency, the infant is taught to be emotionally responsive themselves. Thus, securely attached children grow into resilient, emotionally healthy adults who enjoy emotionally healthy relationships because they generally feel trusting and safe in those relationships.

In intimate relationships, a secure adult feels secure in their connection with their partner (even in their partner’s absence). This allows each partner to live their lives freely (which is called interdependence). Because a Secure individual is aware of and is able to respond in emotionally healthy ways to their own needs, this frees them up to be supportive at times when their partner feels distressed. Also, because a secure adult feels comfortable eliciting care from others, they are more likely to turn toward (vs shutting down or withdrawing from) their partner when they feel troubled.

In other words, an intimate relationship with a secure partner tends to be honest, open and equal, with both parties feeling independent, yet loving toward each other. Because of this, it is unsurprising that we find that compared to the other attachment styles, securely attached adults (and their partners) report feeling the highest levels of relationship satisfaction.

People with a secure attachment style:

- Generally feel close to others

- Feel comfortable with emotional and physical intimacy, and also with independence

- Communicate effectively and resolve conflicts as they arise

- Have fairly stable relationships

- Generally trust in their partner

- Feel safe in being vulnerable with their partner

Secure Attachment Example

A fantastic example of what Secure Attachment ‘looks like’ in the context of healthy (mutually secure) adult relationships is clearly evident in the (now) infamous “A Credo for My Relationships With Others“ by Clinical Psychologist Dr. Thomas Gordon. As you read through this Credo, I invite you to reflect upon whether you are achieving something like this within your important primary relationships (and if you are, reflect inwards about whether your are achieving this same harmony and respect internally – between the competing aspects of yourself):

A CREDO FOR MY RELATIONSHIPS WITH OTHERS

You and I are in a relationship which I value and want to keep. Yet each of us is a separate person with our own unique values and needs and the right to meet those needs.

So that we will better know and understand what each of us values and needs, let us always be open and honest in our communication.

When you are having problems meeting your needs, I will listen with genuine acceptance and understanding so as to facilitate your finding your own solutions instead of depending on mine. And I want you to be a listener for me when I need to find solutions to my problems.

At those times when your behavior interferes with what I must do to get my own needs met, I will tell you openly and honestly how your behavior affects me, trusting that you respect my needs and feelings enough to try to change the behavior that is unacceptable to me. Also, when some behavior of mine is unacceptable to you, I hope you will tell me openly and honestly so I can try to change my behavior.

And when we experience conflicts in our relationship, let us agree to resolve each conflict without either of us resorting to the use of power to win at the expense of the other’s losing. I respect your needs, but I also must respect my own. So let us always strive to search for a solution that will be acceptable to both of us. Your needs will be met, and so will mine—neither will lose, both will win.

In this way, you can continue to develop as a person through satisfying your needs, and so can I. Thus, ours can be a healthy relationship in which both of us can strive to become what we are capable of being. And we can continue to relate to each other with mutual respect, love and peace.

Dr. Thomas Gordon (1978)

Non-Secure Attachment Styles

2. Anxious Attachment (aka Preoccupied):

Children who had parents who at times responded well to their needs, yet at other times, were not emotionally present or may have responded in hurtful or critical ways, grow up feeling insecure, uncertain of what treatment to expect.

In relationships, adults with an anxious attachment style find that they need a lot of reassurance and responsiveness. Unlike a securely attached person, those with an anxious attachment style may appear overly dependent on their relationships to feel okay. Certain interactions or events may trigger deep mistrust and they may regularly feel heightened anxiety about the stability of their relationships.

Even though anxiously attached individuals may feel desperate or insecure, more often than not, their behaviour exacerbates their own fears (via a feedback loop called a ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’). They may also interpret independent actions by their partner as affirmation of their fears. Worse, when they feel unsure of their partner’s feelings or feel insecure in their relationship, they may become clingy, demanding or possessive toward their partner.

Although these are simply attempts to protect the Self via seeking a sense of safety, reassurance and security, by clinging to their partner or by engaging in behaviours called ‘Protest Behaviours’ a person with an anxious attachment style may unwittingly push their partner away. For example, if (say) a partner starts socializing more with friends, they may think, “See? He doesn’t really love me. I was right not to trust him – Maybe there is someone else… This means he is going to leave me.” This may lead to (for instance) lots of reassurance seeking behaviours, such as calling, texting, or even stalking or reading a partner’s private messages. Alternatively, it may lead to hostility towards that partner, who often will not understand the context of the person’s behaviour, and this may drive them away – particularly if the partner has an avoidant attachment style (below).

People with an anxious attachment style:

- Feel the need for lots of reassurance in a relationship

- Often report feeling overwhelmed or extremely anxious when they and a loved one disagree or argue

- Question their partner’s love (e.g., especially at times when their partner is away)

- Feels threatened by their partner needing a break (and may pursue them until they give in)

3. Avoidant Attachment (aka Dismissive):

Children of caregivers that were emotionally unavailable, absent, or unaware of their needs often develop an Avoidant attachment style. Perhaps crying was discouraged, or perhaps you were belittled for having emotional needs. As an adult, you may feel uncomfortable depending on someone, or being depended on by others.

A person with an avoidant attachment style lives in an ambivalent state, in which they are afraid of being both too close to and too distant from others. In relationships, they have fears of being abandoned but also struggle with being intimate. They may cling to their partner when they feel rejected, then feel trapped (or resentful, as though they will lose their sense of ‘Self’) if they become too emotionally intimate / close.

Often, in relationships, the avoidant style is attracted to the anxious style, and this sets off a push-pull between one partner (the anxious style) feeling unloved and the other partner (the avoidant style) feeling unable to meet the emotional demands of the other.

People with an avoidant attachment style:

- Feel the urge to pull away when their partner is seeking connection or is distressed

- Regularly feel emotionally removed from others

- Want to distance themselves from (vs resolve) stressful situations or conflict

- Are generally uncomfortable with their emotions. Partners often accuse them of being distant and closed off, rigid and intolerant. In return, they may accuse partners of being too needy.

- May prefer fleeting, casual relationships to long-term intimate ones, or may seek out partners who are equally independent (or who will keep their distance emotionally).

If you have an Avoidant Attachment Style, it is important to respect (and be able to communicate) your needs for space in a relationship. One way of doing this is to use phrases that contain elements like: “This is not a reflection of how I feel about you – this is something that I need”.

4. Disorganized (unresolved) Attachment:

Disorganized attachment is the primary style common in survivors of complex developmental trauma (cPTSD). For instance, perhaps a caregiver was frightening, abusive, or behaved in highly inappropriate ways; perhaps a child’s human rights were violated. These traumas can cause fear of a parent and/or deep confusion in a child (remember – human children are born dependent on their caregivers for nurturance, safety, shelter, sustenance etc) will develop the understanding that a parent is not present for them. However, this creates an internal dilemma: A child is completely dependent on their parent for food, safety and shelter. Often, a child’s innate desire for parental love may create an inner conflict whereby they believe that the behaviour of the abusive parent is their own fault, or that they should remain loyal because “they are my parents”. As an adult, a person with a disorganized attachment style may long for closeness, but may also fear it. They may not seek out relationships because they may feel like counting on others is unsafe. When presented with opportunities for closeness, they may pull away.

People with a disorganized attachment style:

- May have had primary caregivers that were abusive (physically, emotionally, sexually, neglect etc)

- Commonly report craving emotional intimacy, but also feel it is safer to be alone

- May have had primary caregivers who showed love one minute but who were frightening the next

- May have Complex Trauma (cPTSD)

- May have a deep mistrust of others or question their positive intentions

Attachment & Emotion Regulation

Emotion regulation is the process by which we influence how we experience and express our feelings (which emotions we have, when we have them, and how they are expressed). Throughout our lives, emotion regulation is an important regulator of interpersonal relationships and in our relationship with ourselves.

The ability to regulate one’s emotions is taught in one’s earliest relationships. We are taught ‘how’ to feel (and we are often not taught how to feel) by our primary caregivers, and this becomes ingrained throughout childhood, and practiced throughout life. Thus, emotion regulation and quality of an infant’s attachment are closely linked.

In infants, patterns of emotion regulation are shaped and developed in direct response to experiences with their caregivers. Because an infant is dependent on a caregiver (e.g., for food, shelter, and protection), an infant’s emotional regulation serves the important function for the infant of maintaining a close relationship with the attachment figure. This ensures that the parent will remain close to the child and the child will thereby (hopefully) be protected. As was demonstrated in the “Still Face” videos above – this is a survival instinct (we are hard-wired to do this).

Therefore, it is easy to understand how infants of non-secure parents, who may experience repeated rejection, or hostility, may learn very quickly to minimize their own negative affect (i.e., by emotionally withdrawing or shutting down) in order to avoid the risk of further rejection. Often, infants internalise the voices of their parents – and this can lead to an internalisation of this response to self that persists into adulthood in the form of negative self-beliefs and/or self-criticism.

On the other hand, it is easy to understand how infants of mothers who have been relatively inconsistently available may maximize negative their affect in order to increase the likelihood of gaining the attention of a frequently unavailable caregiver. If this strategy succeeds, it becomes engrained through repetition as a natural response whenever faces with a similar situation. Clearly, this could result in difficulties with emotion regulation for the child that may persist into teenage years and adulthood.

Again, both of these patterns of emotion regulation are simply examples of primal attempts by the infant to remain in positive connection with the caregiver. When these patterns work, they are repeated and they become deeply learned emotional responses – ways that we may still strive to have our emotional needs met as adults.

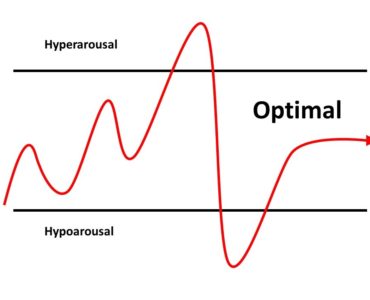

The early experiences you had with your primary caregivers ALSO play a direct role in the development of your brain, which in turn influences your ability to regulate your emotions. Insecure or inconsistent styles of attachment result in the experience of feeling overwhelmed and unsafe in a child, which creates either Hyperarousal (being on high alert) or Hypoarousal (becoming numb) as means of protection. Left unaddressed, this can persist across the lifespan and can greatly affect adult relationships, including our relationship with ourselves.

Over time, these learned protective behaviours can reorganise a child’s brain during a particularly crucial stage of development (0-15 years) and this, in conjunction with either adverse childhood experiences, skills deficits, or maladaptive coping strategies, can lead to difficulties with emotion regulation in adults (such as a reduced Window of Tolerance, discussed in detail here). Essentially this is because through interacting with an infant in a very critical period of brain development (especially between 0 to 12mths) the mother begins to teach and shape how to down-regulate negative emotions but ALSO how to up-regulate positive emotions (such as joy, interest, excitement, which are important for play-states and the development of the dopaminergic-reward system).

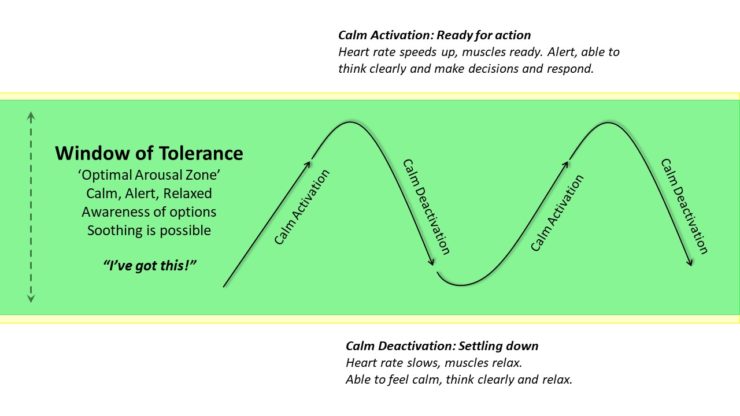

This is essentially what we as adults are ultimately required to do for ourselves, in terms of regulating our emotions (by calmly activating and deactivating our arousal) in response to the full range of events and challenges that we experience. This is depicted in a simple way in the following diagram (taken from my Window of Tolerance article, discussed in detail here):

Moreover, we know that the broader the range of emotions a child learns to experience (and respond to), the broader the range of emotions the adult will be able to understand, experience, and respond to (and understand, experience, and respond to in others).

For these reasons, it follows that, whereas skills for emotional regulation may come significantly easier to those who have grown up with secure attachment, emotional regulation can be more difficult to learn for those who grew up with inconsistent, unavailable or abusive caregiving. Nevertheless, the good news is that we can learn to work with (and heal) our wounded attachment systems, and regarding improving our emotion regulation – this essentially involves developing a new set of skills, which can be learned.

Effects on Relationships

In fact, this primary attachment style is so fundamental to how we process and make sense of the world that we even dream according to our primary attachment style. In one study, participants completed established measures of attachment to determine which attachment style best characterized them. Then, raters who were blind to the test results, listened to the participants’ recollections of dreams (listening carefully for themes, key people and the relationships between them). Amazingly, raters were able to correctly categorize participants’ attachment styles with a very high degree of accuracy, simply based on the content of their dreams (!). This result as been replicated in similar research.

In the area of intimate relationships, both male and female adults seeking long-term partners often identify qualities of responsiveness consistent with Secure Attachment caregiving (such as warmth, attentiveness, and sensitivity), as the “most attractive” qualities in potential partners. Yet, as you are probably aware, despite the attractiveness of these secure qualities, not all adults are paired with secure partners.

This is because it is common for people to find themselves in relationships with partners who confirm their existing attachment experiences regarding relationships, care, and love. In other words, as adults we are subconsciously drawn towards partners who replicate the attachment dynamics that we experienced as children – even when these dynamics are not helpful for us. (This is because our ancient brains are drawn to this ‘familiarity’ on a primal, subconscious level).

However, this need not be the case. If you are in a relationship that contains unhealthy attachment dynamics, you can become aware of them and work with your partner (or with a therapist) to improve and change unworkable patterns. Or, if the dynamic is truly dysfunctional and toxic, you can work towards terminating an unworkable relationship.

Alternatively, if you are not in an intimate relationship (or if you are not seeking one), understanding your Attachment style is still hugely important because it strongly influences how you relate to yourself and communicate with (and understand) others.

It’s Not Your Fault

As discussed earlier, there are many reasons a parent may struggle to be emotionally present with their children. For the most part, most parents try as best as they can to deal with the challenges of parenting with the emotional regulation skills that they have, many of which were passed onto them by their own parents.

Unfortunately, children of parents who lacked the capacity to understand how what they are doing was ultimately affecting their child’s psychological growth and well-being, will most likely be those who have the deepest attachment wounds (and challenges managing relationships, including their response to emotions and needs of the Self). This is because, as humans, we have built-in survival instincts. As infants, our attachment style was our best means of self-protection.

If you align with a “non-secure” attachment style, it is not because you did something wrong. Rather, your attachment style results from surviving your upbringing. In other words, a ‘non secure attachment style’ is a response to this period because it was how we learned to “balance out” the challenges of the caregiving provided to us. Any non-secure attachment style we may develop was the best way we to could cope with the difficulties of circumstances we were handed. In other words, our attachment experiences are not our fault (!). We did not choose our families, nor did we choose the difficult early childhood experiences we were exposed to.

No matter which attachment style you currently have, know that secure attachment is possible. Learning about attachment is a journey of healing, self-compassion, and moving towards a more secure attachment style that will ultimately lead to healthier, more rewarding relationships.

You can recover from your attachment wounds. You can learn to develop new ways to relate to yourself and to connect with others. Learning about attachment by reading this article (and some of the articles at the bottom of this page) marks the beginning of this journey…

Healing Your Attachment Wounds

We now know that the attachment style you developed as a child based on your relationship with a parent or early caregiver does not have to define your way of relating to yourself, or to those you love in your adult life. In fact, we know that healing our attachment wounds is possible through heathy, emotionally corrective relationships.

We know that healthy attachment to others is our primary protection against feelings of helplessness and meaninglessness. For instance, close, connected relationships can actually reduce anxiety and fear by easing our primal fear of abandonment. This is because strong, attached relationships reduce feelings of fear (threat activation) and help “calm the brain”.

Whereas emotional isolation is more dangerous for health than smoking or a lack of exercise (e.g., people who live alone experience three times as many strokes as those who are married), those who feel the safety of a comforting relationship actually are more resilient in life and can go out and take more risks. Quite simply, loving and being loved makes one stronger. Those who have trust in each other can turn to each other in times of distress and this creates even more emotional safety.

Emotionally corrective relationships can be intimate relationships that you may have with a trauma-aware emotionally supportive partner (or a close friend) who either has a secure attachment style or who has done a lot of this work in therapy themselves. This person may be willing to hold space for you while also holding you accountable, as you work through the pain of your past together in all the ways that this may emerge within the dynamics of your relationship. Again, these individuals are often people who have often already done the work of therapy and have done the work of breaking their attachment patterns. However, these relationships deserve to be cherished and they are not a complete substitute for working with a professional who is trained in helping people heal from attachment wounds.

Unfortunately, for people with complex attachment wounds, developing a secure relationship with the ‘right kind of person’ who is emotionally safe, knowledgeable, patient, unconditionally non-condemning and capable of providing a consistent secure base is a huge task, and there will likely be many hurdles along the way. Attachment patterns can be very challenging to understand and very resistant to change, and this can put significant strain on relationships. Again, working with a professional who is trained in helping people heal from attachment wounds is highly recommended.

Although self-help information can be useful, it is also important to seek help for attachment difficulties and not to rely on self-help material alone. This is because attachment is relational, it involves your brain’s development and emotional learning in the context of interactions with others. The learning, reflection, and healing that is needed to address issues of attachment require an emotionally-attuned and emotionally-safe therapeutic environment in which to do this work, and to practice interpersonal skills that cannot be mastered alone.

Developing Secure Attachment

Seen, Soothed, & Safe = Secure Attachment

Secure Attachment can be BEST summarized with the concept of: ‘Seen, Soothed, & Safe’. Although this idea was initially developed by Dr. Dan Sigel (Neuropsychiatrist, Researcher, and best-selling Author) to help simplify Attachment for parents seeking to understand, attune to, and provide for their child’s emotional and developmental needs, the concept of Seen, Soothed, & Safe can be applied to two further areas: How we as adults relate to others and more importantly, how we relate to (and care for) ourselves.

Seen

‘Seen’ means to acknowledge and understand the mind, and emotions of another. This involves showing interest, empathy and curiosity about the feelings, perspectives and needs of another and being supportive an responsive to the emotional worlds of another person (it is the opposite of a dismissive parenting style that ignores, invalidates, or belittles a child for having the feelings or reactions that they might be having). It also requires being able to remain ‘present’ with and attuned to another person. This is not simply about eye-contact; it is about any actions you can take that may communicate to another person that you ‘get it’ at a ‘feeling’ level – that you truly understand their emotional experience. Mindfulness skills, Active Listening skills, and checking that you have heard what someone is saying correctly, can greatly help with this.

Appling ‘Seen’ to Ourselves: This means developing awareness of our own internal worlds, being able to identify, understand, and take responsibility for working with our emotions. It also means identifying and understanding what we need, and being interested and willing to respond to meeting those needs. If this learning was not provided to us by our primary caregivers, this may require therapy and practice.

Soothed

‘Soothed’ means to provide a sense of comfort and calm to another when they are experiencing difficult emotions or situations, in order to help settle and soothe their nervous system, to provide emotional support, or to provide a ‘space’ to be with the difficulty that they may be experiencing. Soothing may be enhanced by the ways we use our voice (tone, speed, expression), and/or physical gestures like body language, eye-contact, hand holding, or hugging.

Applying ‘Soothed’ to Ourselves: Being able to comfort and care ourselves by responding to our needs with healthy self-care actions, that support, settle, and soothe our nervous systems are all hallmarks of being able to provide a sense of ‘soothed’ to ourselves when we are having difficulties. This may require the prior development and practice of self-regulation skills learned in either therapy or via useful self-help tools.

Safe

‘Safe’ means to provide a sense of emotional availability and/or protection to others which can be demonstrated in a variety of ways, such as via the aforementioned ‘Seen’ and ‘Soothed’ actions, by being ‘present’ and attuned to their inner worlds and demonstrating that you can be a stable and dependable figure during in times of distress. Other actions that cultivate a sense of ‘safe’ may include: Being able to provide emotional a ‘space’ for others where they feel accepted when experiencing their difficulty, by being reliably accountable for one’s actions where there is a contribution to the difficulty (i.e, taking appropriate responsibility to ‘right a wrong’), and checking-in on how another person is feeling in a reliable and a consistent way.

Applying ‘Safe’ to Ourselves: In addition to the skills required to feel we are ‘seen’ and can ‘soothe’ ourselves, being able to communicate through our intentions and our actions that we can care for ourselves in healthy ways (no matter what we may be feeling) can provide a deeper sense that we are ‘safe’ within ourselves. This is largely achieved by being able to respond to our inner worlds consistently with care, acceptance and compassion. This demonstrates to us that ‘it is OK’ to feel what we are feeling. Being proactively responsive to our emotions and our needs (which may include taking assertive actions to elicit care from others) and assertive communication skills are additional resources that can contribute to our sense of ‘safe’.

The video below summarizes the above concepts. Although it presents them as ‘4’ separate elements, they are essentially just 3 because: Seen + Safe + Soothed = Secure Attachment.

Individual Therapy

A skillful trauma-informed psychologist who has undertaken the appropriate training can offer you the experience of a healthy, emotionally corrective relationship. Such a therapeutic relationship has the potential to be an emotionally corrective relationship partly because it is the therapist’s job to be ethical, consistent, and to build in security while being fully present for their clients.

The goal of therapy in providing a secure attachment is to model healthy ways to relate to others and to provide a safe environment for you to learn to attend to and express your own feelings and needs, while also healing past wounds and practicing new skills. In this way, you can work towards developing more secure ways of relating to others, often referred to as ‘Earned Secure Attachment‘. With the support of your therapist, you will be able to begin to apply these new strengths outside therapy in relationships that matter to you such as with a partner, children and friends. This work can take time – but it can be done whether you are in an intimate relationship, or not.

In terms of using the emotionally corrective relationship of therapy to improve your relationship with yourself (which is also an important part of developing ‘earned secure attachment’), this may involve learning new ways of being able to soothe and support yourself when you are struggling or are experiencing a setback – these emotional skills will likely not have been made available to you as a child. For people with significant developmental traumas (such as attachment wounds or Adverse Childhood Events), therapies such as EMDR Therapy may be useful in helping you to remove the disturbance of painful memories so that you can put your past behind you, and create the relationships with yourself and others that you ultimately were unable to have.

If you are troubled by memories that disturb you, or if you are tired of being emotionally triggered by events, I recommend reading my page about EMDR Therapy.

Attachment-Focused Therapy for Couples (EFT)

The most well researched therapy for couples that makes use of attachment science is called Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) for Couples. EFT for Couples is a short-term therapy that is aims to improve attachment and bonding in adult relationships. EFT for Couples is about creating connection in close relationships. It helps couples to understand and express their emotional experience including their needs, feelings, thoughts, and behaviours.

EFT for Couples is acknowledged as the gold standard for empirically validated interventions in tested interventions for couples. This research shows large treatment effect sizes and impressively, stable results over time.

EFT is the only model of couple intervention that uses a systematic empirically validated model of adult bonding (attachment) as the basis for understanding and alleviating relationship problems. Developed over 30 years ago by Sue Johnson, EFT for Couples is essentially attachment science in a therapy. As has been discussed, attachment science views human beings as innately relational, social and wired for intimate bonding with others. The EFT model prioritizes emotions and emotional regulation as the key organizing agents in individual experiences and key relationship interactions.

Below is a short video explaining research that Sue Johnson and her team performed, involving brain scans of people in relationships who were treated with EFT for Couples. It demonstrates how developing a strong relationship bond can reduce feelings of fear (threat activation) and can help “soothe the threatened brain”.

EFT for Couples not only addresses factors such as relationship distress, intimacy, trust, and the forgiveness of injuries, but it also aims to influence and heal you and your partner’s attachment style.

Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) involves discussing specific incidents that may occur in your relationship, as a way to help each of you learn about your emotions and the behaviours that result from those incidents.

For example, your therapist may discuss your partner reminding you to take out the rubbish and how that makes you feel. Do you feel angry? What else might you feel? Are you ashamed because you forgot, so that makes you want to lash out in anger? Do you feel judged as “not good enough” by your partner and that makes you feel as if you disappointed her? Does this then make you want to pull away from her?

Goals of EFT for Couples:

- To create a positive shift in partners interactional positions and patterns.

- To foster the creation of a secure bond between partners.

- To expand and re-organize key emotional responses and, in the process, the organization of self.

If you are in a relationship in distress, or you would like to improve your relationship in any way, I highly recommend learning more about the work of Sue Johnson and finding a psychologist who can offer EFT for Couples.

For a summary of the research on EFT for Couples, please visit https://iceeft.com/eft-research/

Video explanation of EFT for Couples:

A more in-depth presentation about Attachment and EFT for Couples:

Parents & Caregivers

If you are a parent whose childhood attachment experiences were less than ideal, or worse, perhaps you were exposed to significant traumas commonly referred to adverse childhood events (ACEs), I recommend that you engage in therapy with a clinical psychologist that is trauma-informed, and attachment aware (Please note: Sadly, not all psychologists are). Options for family therapy also abound.

It is also be important to invest in education. My recommendations are to undertake one (or both) of the following established and researched-backed programs:

- Circle of Security (COS) training (external link):

An international program designed for parents and carers of children aged 0-12 years who want to strengthen the bonds with their children and would like support to help their children to build secure relationships. There is evidence that parents can in fact positively change a child’s insecure attachment style to ‘secure’ with COS training.

- Collaborative and Proactive Solutions (CPS) training (external link)

CPS is an evidenced-based model of psychosocial treatment developed by Dr. Ross Greene, and described in his books Raising Human Beings, Lost at School, & The Explosive Child (another highly recommended ground-breaking approach to understanding and parenting children who frequently exhibit severe fits of temper and other significantly challenging behaviours).

Rather than focusing on kids’ challenging behaviours (and modifying them), CPS helps kids and caregivers solve the problems that are causing those behaviours. This problem solving is collaborative (vs unilateral) and proactive (vs reactive). Research continues to find that that the model is effective at not only solving problems and improving behaviour but also at enhancing adaptive communication and emotion regulation skills.

- The Attachment Project (external link):

The Attachment Project is a (for profit) organisation that has useful Self-Help information for parents & caregivers (such as the specific link above) to help better understand how the different attachment styles develop in response to specific parenting strategies and styles. Their content is written by psychologists.

However, they offer an Attachment Style ‘quiz’ that is not a reputable diagnostic tool, nor is it empirically-validated (if you take this quiz, do so with ‘a grain of salt’). To their credit, the do state “The Attachment Project’s content and courses are for informational and educational purposes only. Our website and products are not intended to be a substitute for professional medical and/or psychological advice, diagnosis, or treatment.”

Summary:

- Attachment science explains how humans develop and function in relationships across the lifespan.

- Our ‘Attachment Style’ relates to the quality of our relationships with our primary caregivers.

- Our earliest attachments with parents or caregivers shape our abilities and expectations for relationships throughout life. The quality of our bond within these early relationships influences how our sense of Self develops, what we expect from our partners, and how we believe relationships work.

- Our early attachment experiences influence: How our brains developed; how we learned regulate our emotions in response to stress; and, how we relate to others and ourselves (including the partners we choose and how we believe relationships work, and we behave in relationships).

- Attachment styles are not our fault (or our choosing). Rather, they emerge early in our lives and are the result of previously ADAPTIVE, self-protective (i.e., ‘survival’) behaviours, that we developed in response to our upbringing. These patterns are often carried forward into adulthood, even though the resulting effects on our relationships with ourselves and others may be compromised or may become ultimately unworkable.

- Parents do not necessarily have to be highly abusive to have a negative effect on their children. Parents who are over-protective and intrusive, who are judgmental and have high expectations, or who are dismissive of a child’s thoughts and feelings can also cause a distrust of relationships – or even a distrust of a child’s own emotions – well into adulthood for that child.

- Attachment in conjunction with adverse childhood experiences and other developmental deficits (resulting in difficulties with emotion regulation or maladaptive coping strategies), can lead to difficulties with emotion regulation in adults (such as a reduced Window of Tolerance).

- Healing our attachment wounds is possible through a combination of learning, self-reflection, and heathy ’emotionally corrective relationships’ – this includes therapy with a trauma-informed, attachment aware therapist with whom you feel safe, understood and respected.

- Although self-help information can be useful, there is a need for safe guided reflection and learning of interpersonal skills that cannot be mastered alone.

- Because attachment is relational, we need an emotionally-attuned and emotionally-safe therapeutic environment in which to do this work. It involves working with our emotional understanding and responses in the context of interactions with others.

- Therapies such as EMDR Therapy may be useful in helping you to remove the disturbance of painful memories so that you can put your past behind you, and create the relationships with yourself and others that you ultimately were unable to have. Regardless of the therapy ‘type’, ensure you seek the help of a therapist who is trauma-informed, and attachment aware.

- Help for parents abounds in terms of individual and family therapy, and research-backed programs mentioned above in this article.

- Couples with attachment difficulties are recommended to invest in therapy with a therapist who is trained in Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) for Couples. Based on attachment science, EFT is the gold standard for couples therapy a therapy. EFT for Couples not only addresses factors such as relationship distress, intimacy, trust, and the forgiveness of injuries, but it also aims to influence and heal you and your partner’s attachment style.

- Understand that your attachment style may also affect how you engage in therapy. If you are receiving (or are planning to receive) therapy, I recommend reading the following article: How to get the most out of therapy.

Further Resources:

- How Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) impact on attachment, brain development and later lifestyle and health risk factors

- Your brain’s 3 Emotion Regulation Systems

- Getting Past Your Past with EMDR Therapy

- Emotion Regulation skills: Understanding your Window of Tolerance

- How to get the most out of therapy

- A list of all articles that I have written