Your Brain’s 3 Emotion Regulation Systems

Overview

Evolution is a powerful force that continues to shape and develop our bodies and brains. Indeed, the human brain has evolved in clever ways that have given us cognitive abilities that no other species has. For instance, the human mind is capable of overcoming hugely complex challenges in the physical world. However, unlike other animals, our evolution has led us to inherit a (partially) flawed system: We are stuck with a brain that we did not design and this inherited ‘evolved’ brain is capable of creating intensely negative and reactive emotions that many of us find very difficult to understand or manage. Worse, this often contributes to us reacting in ways we do not necessarily want and we may even direct these intense negative emotions at ourselves (!).

We can become triggered by unwanted anxieties about the future, we can be haunted by pains of our past (making them feel as though the past is happening again NOW), and we can attack ourselves with our ‘inner-critics’. We can become distracted by greed (at the expense of us being the best versions of ourselves that we can possibly be), and we can become fixated on the unrelenting pursuit of goals that do not truly matter (in an attempt to avoid aspects of ourselves that we to not want to acknowledge). All of these can lead us to behave in unworkable ways that may make situations worse for ourselves or others (!).

On this page you will learn about how our minds are wired, and why we do many of the things that we do, and how mental health difficulties emerge and are maintained. You will then be well-placed to learn ways to soothe your Threat and Drive systems and generate a sense of calm, comfort, peace and resilience, so that you can be more free to choose how you respond to challenging emotions (such as anger, fear, pain, disappointment, sadness, and loneliness), difficult internal experiences (e.g., painful memories, negative predictions, anxiety-based imagery, or harsh judgements and self-criticism), and any other situation that you may find personally challenging.

Although the information on this page is specific to the brain’s 3 emotion regulation systems, there are also many important individual factors that contribute to how these systems function (and how challenging it may be for an individual to regulate these systems). Importantly, we find that the common fears, blocks, and resistances that individuals often have around helping themselves work through difficult emotional experiences, are directly related to these developmental factors.

In particular, we know that the quality of the attachment bond between an infant and primary care giver shapes brain development and contributes to a person’s emotional regulation capacities (and this in turn influences relationship difficulties that they may encounter in adulthood – with others and with the Self). Similarly, we know that exposure to adverse events and toxic stressors in childhood play a role in brain development, coping skills, and resilience. Finally, it is important to appreciate how both of these factors relate to our Window of Tolerance, which is loosely defined as the zone of arousal in which we are able to function most effectively given the demands of every day life.

As you read on, I encourage you to reflect on how your childhood experiences (mentioned above) may have impacted on your emotional learning and the development of your brain’s 3 emotion regulation systems. Links to all related articles will appear again throughout this article.

Our Tricky Brains

Our brains have evolved to enable us to solve amazingly complex problems: We can create cures for medical issues, we can send humans into space, and we have created amazing technologies (like smartphones and the internet) which allow us to learn, connect and be entertained. Despite the evidence of our prowess over the physical world, we are still no closer to solving the problems of our inner worlds. We cannot use the same problem-solving logic that works in the physical world to permanently address the internal suffering we can experience in our inner worlds.

Our ‘tricky’ brains have been shaped by evolution for us (not by us). So many of the difficulties humans experience are not things that anyone would ever think to include if they were asked to re-design a brain from scratch. Think about this: Our tricky brains can produce scores of unwanted thoughts, unwanted images and unwanted emotions (and thousands of these events can happen on a daily basis!). Yet, we did not choose to have brains that function in this way. Equally, we may struggle with conflicting motivations or desires that may not be helpful. Again, we did not choose to have brains that function in this way (it’s not our fault – evolution shaped our brains this way).

We can become triggered by unwanted anxieties about the future, we can be haunted by the pains of our past (making them feel as though the past is happening again NOW), and we can attack ourselves with our ‘inner-critics’. We can become motivated by greed (at the expense of us being the best versions of ourselves that we can possibly be), and we can become fixated on the unrelenting pursuit of goals that do not truly matter (in an attempt to avoid aspects of ourselves that we to not want to acknowledge). Yet, we did not choose any of this.

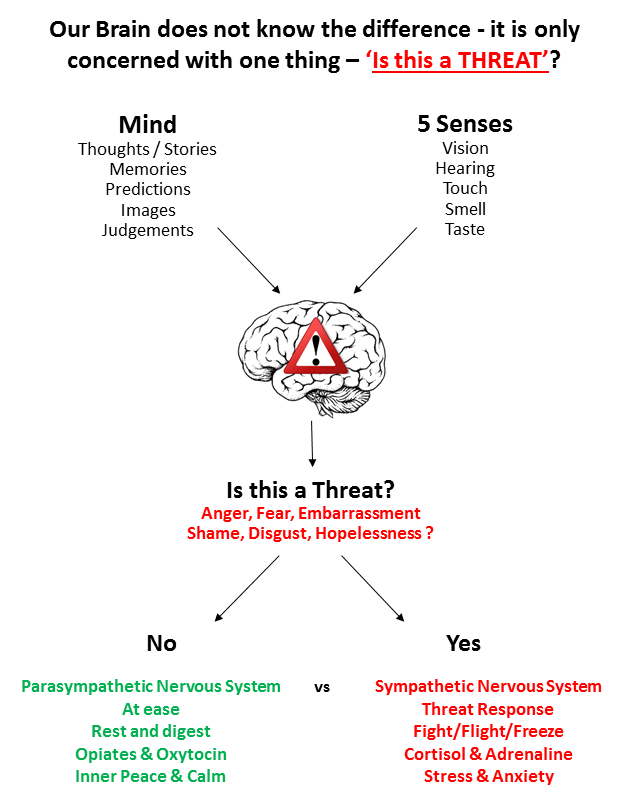

As discussed in greater detail in the articles how to deal with negative thinking and the Threat System, our brains respond to external threats and internal threats in exactly the same ways:

In addition to the way evolution designed and shaped our tricky brains (which we did not choose), we also did not choose our family of origin, nor did we choose any of the adverse life experiences that have shaped us. We all have brains that respond to ‘perceived threats’ in extremely powerful ways, and we all have brains that have been affected (for better or for worse) by our upbringings. For instance, we know that our early attachment bond with caregivers provides emotional learning experiences that shape brain development and emotion regulation, and that the impacts of these experiences can continue throughout adulthood (e.g., how much we perceive others as predictable and trustworthy, how we relate to others in relationships, and how we care for ourselves during times of distress).

Yet, despite all of this, just as we are responsible for what we make of our lives, we are all still individually responsible for how we regulate our emotions and respond to our tricky brains and life’s challenges. Moreover, it could be said that we are all united in this life together by several themes: We all experienced being born, and we all will experience dying. We all have hopes and dreams. We will all experience pains, fears and sadness. We will experience joys, and we all will experience setbacks, disappointments and difficulties. In other words, our evolution, ‘tricky brains’, and our common humanity (with all of its ups and downs) unite us all.

By keeping in mind just how tough life can be for us all at times, we are more likely to be able to access the best versions of ourselves to support others (and ourselves) in times of distress. However, being the best version of ourselves also requires that we fully understand how our own tricky brains are wired. This means understanding how our motivational systems (and the bugs and feedback loops in the brain caused by evolution) mix with our personal life experiences to shape our perception of the world, ourselves and others.

The 3 Emotion Regulation Systems

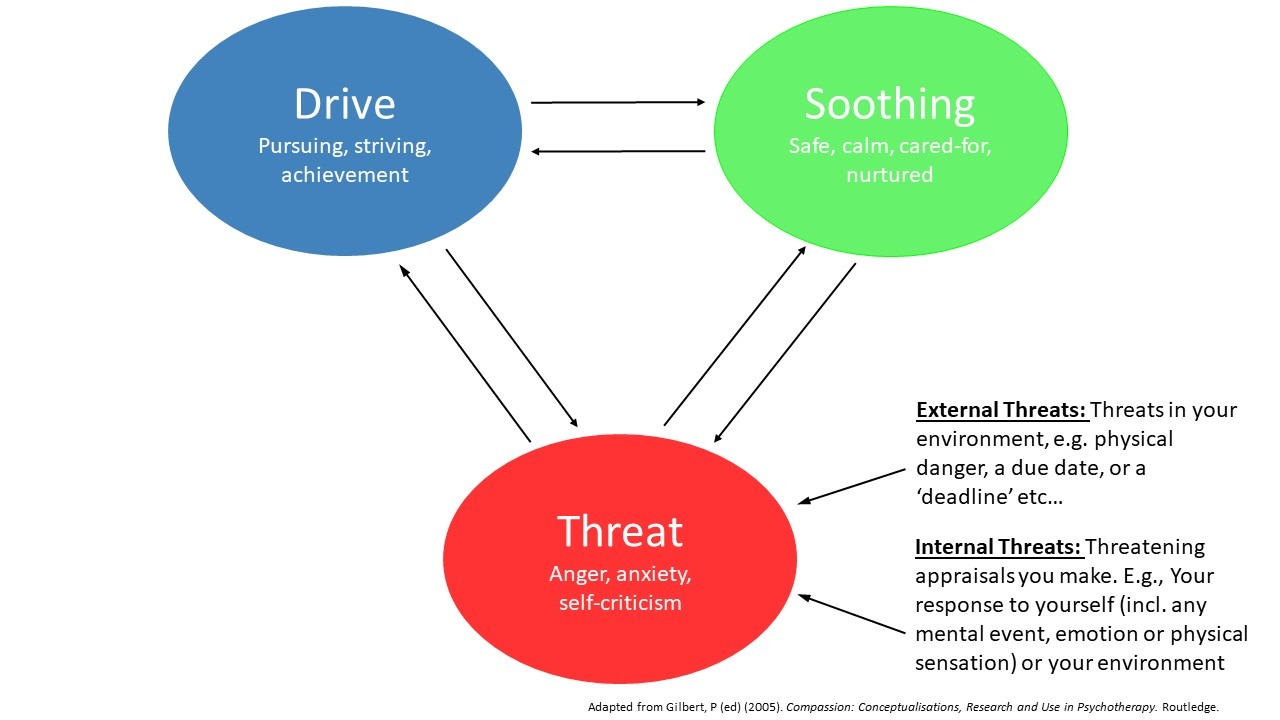

Professor Paul Gilbert (who has been knighted Order of the British Empire for his incredible contribution to the field of Psychology) proposed that we have three main kinds of emotion regulation systems, and that adverse early experiences can lead to an unbalance between these systems. This leaves us sensitized to distress caused by fears and anxieties; self-criticism caused by failures; and, deep feelings of shame about things we have done, and/or about things over which we had very little control.

Although we all manage our emotions by switching between the following systems, as will be discussed, most psychological difficulties are caused by an overuse of the Threat and Drive systems (and an under-use of the Soothing system) to manage both actual and perceived threats.

The Threat System (Detection & Protection)

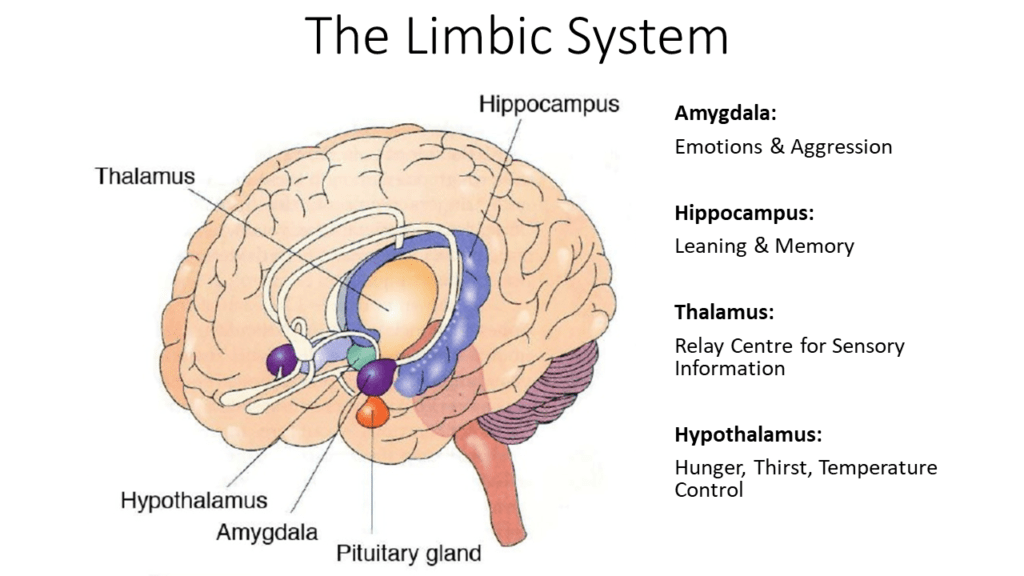

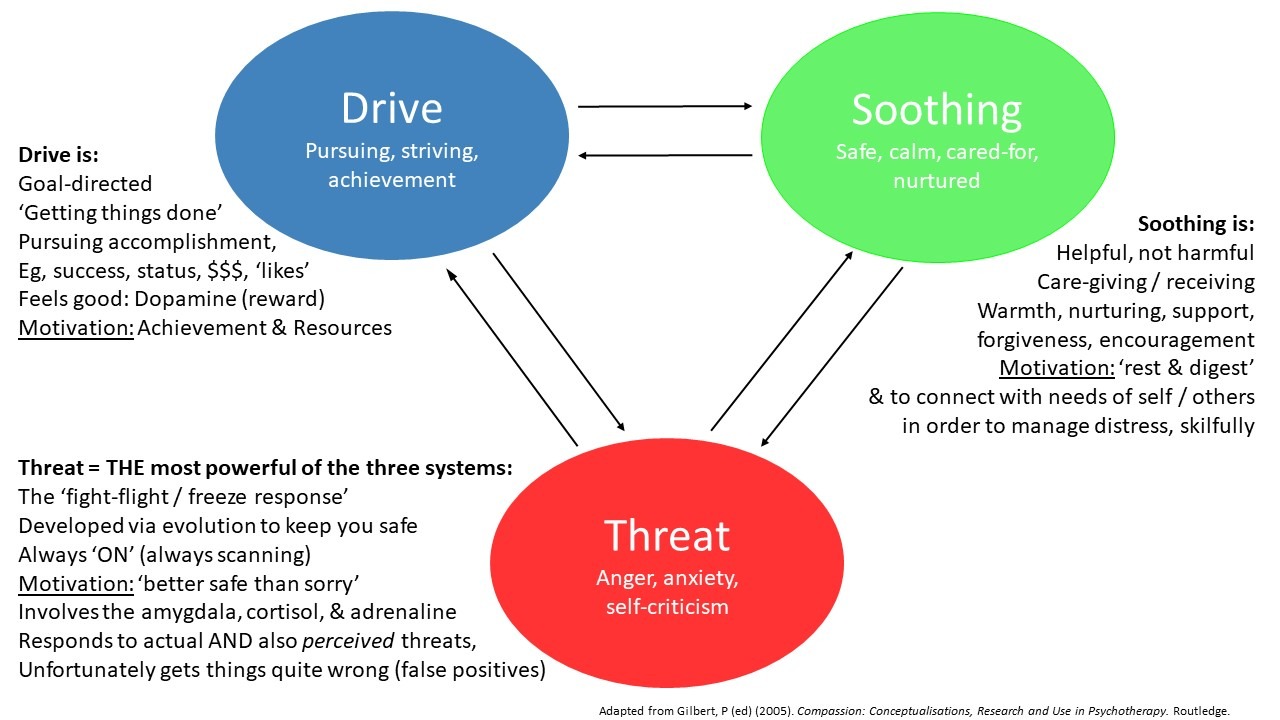

Our Threat System is very powerful: it involves stress-hormones such as Cortisol and Adrenaline. It can activate powerfully motivating bursts of arousal that can alert us to threats and can motivate us to take action. The Threat System responds to external inputs (i.e., problems in the external world) and also internal inputs (e.g., imagery, emotions, thoughts, memories, judgments, predictions etc). It does this by creating powerfully motivating feelings of anger, anxiety, fear or aversion in response to potentially threatening stimuli. The behavioural ramifications include: the Fight-Flight response (which leads us to attack or withdraw), to ‘freeze’ or submit (which can both lead to feelings of shame), or to engage in self-attacking and self-criticism.

The Threat System has been fine-tuned by evolution over thousands of years (those with better Threat Systems were more likely to survive long enough to pass on genes and help raise young). This means our brains have evolved to detect threats very quickly and to mobilise a response (by diverting our energy and attentional resources toward eliminating the threat). This all happens very quickly to ensure our ultimate survival (think: ‘survival of the fittest!’). The Threat System has thus been shaped by evolution to keep us safe. It operates on a ‘better safe than sorry’ principle – it is reactive because its aim is to protect us (to keep us alive), by scanning for and identifying all kinds of threats (even if it gets things wrong, sometimes – which it does!).

Research shows that we are biased toward processing threat-based information: We know that negative information captures our attention, thinking, and memory much more powerfully than does positive information (this is referred to by researchers as a ‘negativity bias’). For instance, we feel the sting of being reprimanded much more powerfully than we feel the joy of praise. We also know that threat-based emotions (fear, anger, disgust) organize our brain and bodies in powerful ways that motivate us to ‘protect’ ourselves and ‘eliminate the source of threat’ in order to ‘stay safe!’. And this all makes perfect sense, from an evolutionary point of view (remember: ‘survival of the fittest’!).

Although this may have been very helpful when having to fight a saber-toothed tiger or a dinosaur, in modern times, it is terribly unhelpful when we are faced with: Having emotions or memories that we would rather not have (e.g., trying to forget the painful past); when we are anxious about trying to solve future problems; when we are trying to do something completely incompatible with Threat, such as when we are trying to stay present and connect with others (or when we are simply lying in bed trying to fall asleep!). What ends up happening is our Threat Systems hijack the situation and worse, if we cannot solve the problem – WE may become the source of the problem (and the target of our Threat System).

So, when balanced with the two other systems, the threat system helps alert us to potential threats and obstacles, and helps to help keep our lives moving in desired directions. However, because it is one of the brain’s most powerful system (remember: it’s all about survival!) it is easy for this system to take up more than its fair share of mental and physical energy. Due to our brain’s ability to imagine and ruminate, and because the Threat system responds to internal inputs (like imagery, thoughts, memories, judgements, predictions etc), it is possible to keep this system running even in the absence of any actual threat. This means that if we spend lots of time living unnecessarily in a state of ‘threat’ our worlds will be experienced as a potentially unsafe. This can make the world seem an unnecessarily anxiety-provoking, exhausting, or an overwhelming place to be. This can lead to toxic stress and a range of mental health difficulties.

You can read more about your brain’s threat system and its triggers, here.

The Drive System (Pursuit, Resource Acquisition & Achievement)

The Drive System is a motivational system that also has roots in our evolution, in that it drives us towards the things we want or need (or, at least, things that we believe we need) in order to prosper. The Drive System alerts us to opportunities for pursuing goals and securing resources, and helps us focus and maintain our attention on such pursuits. The Drive system is highly influenced by the pleasurable brain chemical Dopamine. Our Brains produce Dopamine (experienced as ‘pleasure’), whenever we are either in pursuit of a chosen direction or when we achieve something that we set out to achieve. In other words, the drive system is being utilized whenever we pursue OR when we achieve our goals.

Like the Threat System, the neurochemistry involved in the Drive system can be powerfully motivating and can narrow our attention to focus on whatever we are pursuing – but this can become tricky especially when the blind pursuit of our goals is actually causing harm to ourselves or others. So, the Drive System can lead to engaging in life-enhancing, workable, values-informed activities BUT it can ALSO inadvertently lead us to taking actions that can reinforce our problems.

The Drive System alerts us to opportunities to pursue goals, and it can help us focus and maintain our attention on such pursuits. In the Animal Kingdom, Drive looks like this: The quest to secure Food, Shelter, Comfort, and Territory (e.g., a bird focused on finding sticks to build a nest, a squirrel hoarding acorns for the winter, dogs fighting over a bone, spiders building a web etc). For humans living in modern societies, Drive looks like this: The quest for Wealth, Social Rank or Status, Competitiveness, anticipation of (and the engagement in) highly valued pleasurable events such as consuming high calorie foods and other forms stimulation (eg video games, internet or pornography, illicit substances), or achieving success (either ‘socially prescribed’ success or however else we may define and value it, ourselves).

In other words, in humans, the Drive System is associated with the anticipation of a positive outcome, accomplishment aka via ‘Getting Things Done’ (doing more, being more, earning more, & having more) and / or achievement (such as earning a higher rank socially or in the eyes of others in our social group). In other words, even simply engaging in the process of accomplishment can be experienced as rewarding.

When in balance with the other two systems, the drive system can help keep us activated in the pursuit of important life goals. However, at the extreme, Drive can lead to addictive and compulsive behaviours (e.g., chasing unrequited love or the ‘high’ associated with drugs, or compulsive behaviours people engage in order to avoid anxiety), much like the addictive drug cocaine (which also stimulates the dopamine system!). The Drive System often also leads people to overcompensate for feeling bad about themselves which can lead them to pursue achievement in unrelenting and rigid ways (causing perfectionism / control issues, stress, burnout and depression).

Free Dopamine: The Darkside of Drive & Habit Formation

As you will discover, Drive processes can become very problematic for us in terms of ‘habit formation’. This is because the reward system that is activated in the brain when we receive a reward is the same system that is activated when we pursue a goal in anticipation of a reward. It is this combination – anticipation and accomplishment – that can activate the Drive circuitry which makes for the pleasure feelings that can shape our behaviours in subtle but powerful ways (sometimes even without our conscious awareness!).

So, whenever we predict that an opportunity will be rewarding, our levels of dopamine spike in anticipation. And whenever dopamine rises, so too does our motivation to act. Often it is this anticipation of a reward—not just the fulfillment of it— that can drive us to take action. Us pursuing a goal with the lure of achieving the positive outcome we believe it will bring is also rewarding. Thus, we can stimulate our reward system for FREE whenever we pursue any task where we have anticipated a desirable outcome will result – even if this task was set by ourselves (!). Think about how this may play out in some real world examples:

For instance, imagine you ‘decided’ to scrunch up a piece of paper and throw it into a garbage bin from afar. You may assume it will be fairly ‘easy’ and amusing, and succeeding will demonstrate your ‘hand-eye-coordination skills’ and so you anticipate success will bring a positive outcome. Your Drive System has now become activated. You motivation begins to increase. You are now focused – anticipation is fueling your increased attention to this task (your aim, your set-up, your body position, and your ability to block out unnecessary distractions).

Let’s say that on the first throw, you miss (you throw it too far to the left). Frustrated, but determined, you try again. But your second throw is a little too far to the right. Then, you readjust your aim and … ‘BINGO!’ – It lands in the bin with a satisfying ‘THUD’! (You will now likely feel some combination of either ‘satisfied’, ‘accomplished’, ‘pride’ or ‘relief’).

BIG DEAL – all you did was to place a piece of rubbish into a garbage bin (!). But, why did so many positive and rewarding feelings arise during this activity and upon its success ? ANSWER: Because YOU ‘chose’ it as a goal (you decided that it was a worthy endeavour). That you chose a specific way to achieve this goal made it its success highly desirable (!).

Yet, this completely arbitrary (and trivial) example illustrates how we can a) create an arbitrary goal (we can do this with ‘anything’, really), b) stimulate our dopaminergic Drive system with the anticipation of success, and c) experience a reward insofar as pleasurable states in pursuit of the Goal and when finally do succeed! This demonstrates how we humans can use our drive systems to create ‘FREE DOPAMINE’.

This is a trivial example that for most of us would likely only produce a tiny amount of dopamine. But it is instantly possibly more instantly gratifying than (say) so than putting in the effort to reading all of the words on this page (!).

However, here’s where it gets tricky: When combined with the seductive short term benefit (in terms of the feeling of ‘relief’ that comes from a reduction in ‘threat’) that engaging in avoidance behaviours bring, the reinforcing effects of dopamine can quickly become complex habit-forming processes that can maintain psychological difficulties (!).

For example, when someone with OCD succeeds in following a rule they have created, they stimulate powerful reward-circuitry in their brains. They may anticipate future relief (which is ultimately pleasurable) from adhering to a rule that is believed to prevent an aversive situation from occurring in the future, plus relief (further pleasure) when the rule has been successfully followed. When nothing bad actually does happen, if the person associates their actions (rule-following) with a positive outcome this then begins a powerful reward circuit (or ‘feedback loop’) that strengthens the likelihood of this behaviour happening again in similar situations (a habit is formed).

Similarly, when an person with depression and anxiety avoids an imagined future situation that they were anticipating as aversive, they will experience pleasure and relief (even though they were essentially creating this negative situation in their own minds). In this way, ‘avoidance’ is rewarded, and this behavior is more likely to occur again in the future. Equally, when someone with an Eating Disorder adheres to a rigid rule around food (or their weight), the self-prescribed ‘achievement’ that comes from following one’s rule about food is also rewarded by dopamine. Yet, for all of these examples, the rewards are the product of us having created the rules ourselves (free dopamine!).

When it comes to habits, the key takeaway is this: dopamine is released not only when we experience pleasure, but also when we anticipate it. Think for a moment about how you ‘set things up’ to be rewarding in your life? Consider how much dopamine drives of your behaviours – the good (workable, goal-directed approach behaviours) and the bad (your unworkable avoidance-related behaviours).

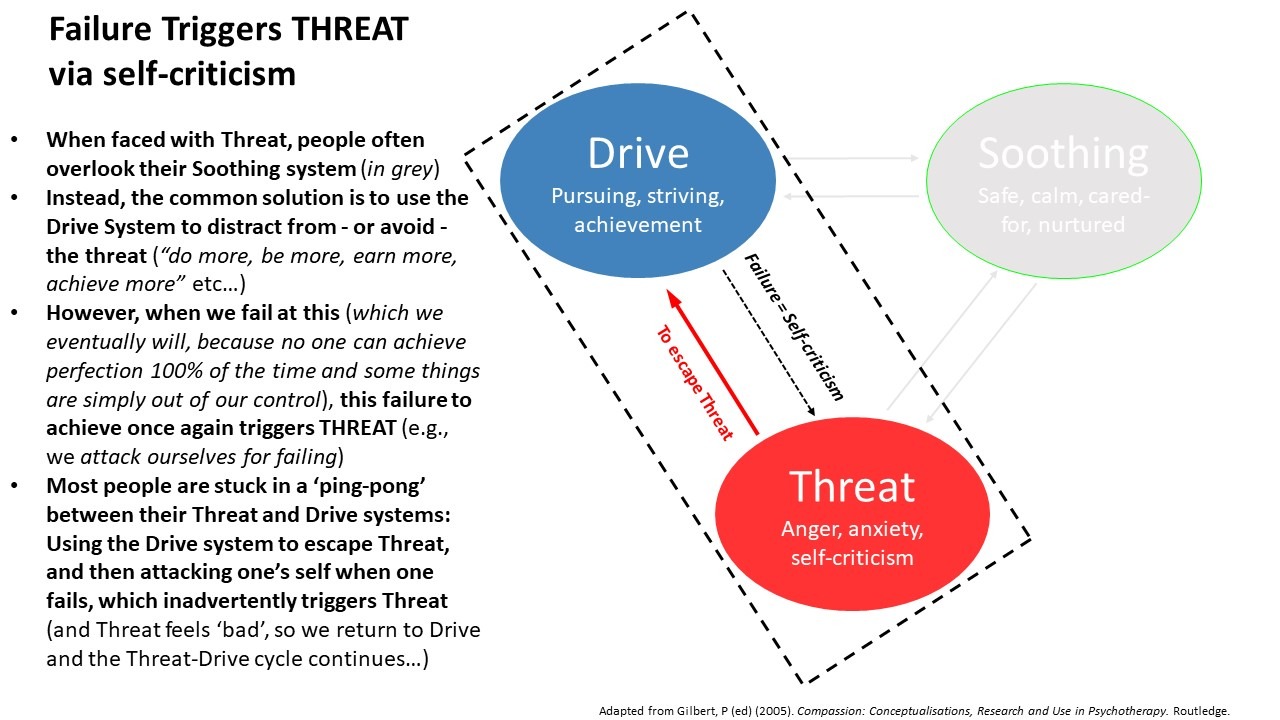

Threat-Based Drive

Many people tend to be stuck oscillating primarily between the Threat and the Drive systems (almost every Drive action that is pursued rigidly is heavily motivated by a deep desire to escape a Threat vs simply pursuing an action for the sake of the pleasure it brings). In other words, many people go between the torment of Threat and its temporary relief via rigid Threat-Based Drive actions. In the short term, this is very rewarding. After all, we are pain averse, pleasure-seeking creatures. However, this cycle can become exhausting in the long term because it leaves no space for failure (because failure triggers Threat), and by extension, no space for peace and contentment with what ‘is’.

However, this can be a very difficult pattern to recognize because it involves these ancient systems. Threat feels ‘bad’ and relieving Threat (via Drive based activities) involves the temporarily distracting effects of the activity and the temporarily rewarding effects of Dopamine.

Politicians and Advertisers know this, and so too should YOU: By triggering Threat, they get you to ‘do’ something (Drive) which makes you feel better about the Threat. For instance, Politicians are often seen attempting to manipulate vulnerable people with messages of “Fear, Threat, Doom… blah, blah … oh, and by the way: VOTE FOR ME!” (This is the ‘Drive’ component of their Threat-based message!).

Advertisers often prey on these evolutionary systems by triggering fears and insecurities (that surprise, surprise: their product is designed to help you alleviate!), or they strive to generate cravings (Drive) in you to buy the next ‘shiny’ object or experience (that you often didn’t know that you needed before you watched the advertisement).

Threat-Based Drive & Mental Health Issues

Many mental health problems involve an overuse of the Threat and Drive systems. For example, we know that individuals with significant depression may experience not only low moods, but also low motivation and negative feelings towards one’s self, tend to overuse their Threat Systems in the form of relying on their ‘inner critic’ to motivate themselves to ‘take action’ (Threat-based Drive). But more than often, what this does is it inadvertently increases their experience of distress (which increases stress hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline), and this makes failure more likely. And because we know that failure triggers Threat (“I don’t like myself AND now I am a failure as well…”), we now have the perfect recipe for agitation, self-criticism, and hopelessness which often leads to self-hatred and suicidal thoughts.

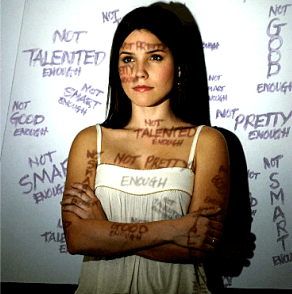

People with “I’m not good enough” / “I’m not Enough” / “I’m a Failure” often utilize the Drive system in unbalanced ways to feel good about one’s self. Although this is understandable, this can lead to problems. For example, by engaging in the relentless pursuit of achievement in order to feel ‘better’ about one’s self (‘do more’, ‘be more’, ‘have more…’), people often over utilize the Drive System and experience high stress as a result. This is because the threat of failing to achieve can trigger threat via feelings of disappointment, shame, and one’s inner-critic, which inadvertently triggers the Threat System. This becomes a never-ending spiral of suffering. Threat-based Drive is always inevitably a recipe for unhappiness, because when you fail to achieve (which is inevitable, because no one can achieve 100% of the time – people make mistakes AND so much is out of our control!) you will trigger Threat – because whenever you come at Drive from Threat and fail, failure triggers Threat via self-criticism.

People experiencing Anxiety commonly use their Threat & Drive systems. Yet, utilizing the Drive System to reduce any threat (‘do more, be more, achieve more’) only produces short term relief . When Drive is used to escape Threat, it often leads to ongoing difficulties. This is because Threat-motivated Drive actions are essentially an elaborate avoidance strategy (they only work until they don’t… then, you’re back at Threat again).

Of course, given that anxiety feels terrible it is completely understandable that people who are experiencing anxiety are often highly motivated to avoid the imminent source of Threat (after all, anxiety feels ‘bad’). However, the avoidance of anxiety (or its triggers) only ever works in the short term – avoidance does not ever completely eliminate anxiety forever, and meanwhile the actions people engage in while avoiding often leads to them missing out on living a meaningful existence.

Moreover, in the long run, avoidance inadvertently results in an increase of anxiety (because we are teaching ourselves we ‘cannot cope’). Meanwhile no skills for managing anxiety are learned, and the Threats continue to circulate in the mind, which results in increased activity in the Threat system. So, although avoidance may reduce anxiety temporarily, in the long run, it makes makes anxiety worse. Unfortunately, this will likely be perceived as a failure (‘”What’s wrong with me!?”) which may lead to self-criticism and hopelessness, which in turn may trigger …Threat (and the cycle continues).

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is also directly related to a ping-pong between the Threat-Drive Systems. Remember the ‘free dopamine’ example in which we created a goal / rule for ourselves to successfully shoot a piece of paper into a garbage bin ? When we succeeded, we felt ‘good’. This is because, set ourselves a goal and achieve it (or whenever we make a rule and stick to it), we will experience FREE DOPAMINE ! ! !

With OCD, people set themselves arbitrary rules to follow. E.g., “I must turn off/on a light 150 times before I can go to sleep, else something bad will happen!”. Often these compulsive behaviours are labelled ‘rituals’. But essentially, they are behaviours derived from a Threat-based Drive rule, in that if someone follows their self-prescribed rule (and succeeds), they will experience relief (dopamine & stress reduction), even though they created the rule, themselves (!). Because Threat does not feel good and because dopamine does feel good, this is a very seductive cycle: a) Feel Threatened, b) Create Rule and follow it, c) Feel relief (or even good) about that! (and thus, …receive dopamine!).

Here’s where it gets tricky: In OCD, when people take the ‘good feelings’ (eg relief) that result from following a rule or engaging in a series of self-prescribed actions as evidence that they are doing the ‘right thing’ (this is called Emotional Reasoning), this leads to a seductive pattern emerging. In the above example of ‘turning on/off a light 150 times to prevent bad things from happening‘, when the relief of performing the action is associated with the observation the following morning that nothing ‘bad’ actually happened during the night, we now have a highly complex and challenging compulsive Threat-Drive pattern emerging (i.e., falsely associating the relief and the possibly even ‘good feelings’ that follow completing a self-prescribed action, along with the fact that ‘nothing bad happened’ – when really, neither are associated).

Although the above example focuses on OCD, it is important to understand that similar processes can also underpin many other psychological difficulties (for instance): the rigid rule-following people can become stuck in when they develop an Eating Disorder, the Threat based safety-behaviours and rituals that can also occur in Psychosis, the ‘protective worrying’ that can occur in Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), and many of the other mental health difficulties people can commonly experience.

So, as you can begin to see – an overuse of the Threat & Drive systems can really get us stuck. The Threat-based Drive ‘ping-pong’ will lead to exhaustion, anxiety, shame, anger, self-criticism, and hopelessness. All of these can have a massive toll our stress levels, our moods, and our relationship with ourselves and others. Clearly there can be no peace with these two systems unless their use is balanced with the third system:

The Soothing System (Safeness, Caring, Contentment)

Like the Threat and Drive Systems, we come into this world hard-wired with Soothing Systems. In evolutionary terms, the Soothing System is our Mammalian Care-Giving System. Often, the Soothing System operates naturally when there are no threats to defend against and no goals that must be pursued. This system taps into feel good neurochemicals such as oxytocin, endorphins, and opiates.

Unlike the Threat and Drive Systems which activate us, the Soothing System can deactivate us. The Soothing System is associated with peaceful states – feelings of being safe, calm, peaceful, and content. The Soothing System allows us to soothe ourselves, and it also allows us to soothe others. It is linked with experiences of giving/receiving care, affection, acceptance, kindness, warmth, encouragement, support and affiliation. We now know from the research that these behaviours can downregulate and weaken the toxic effects of the Threat System. In this way, the Soothing System can bring us a sense of calm, safeness, and peace.

Sometimes people who have been overutilising their Drive Systems have misconceptions around activating their Soothing System because they believe that if they were more accepting of themselves, they would simply ‘give up’ on all of their pursuits and would never achieve anything. This is hugely inaccurate. Whereas Threat-Based Drive is a weakness (it only works temporarily – until you fail – because failure inadvertently triggers Threat via self-criticism), approaching Drive activities from a place of Soothing can provide you with a rich source of strength. If you are able to support, nurture and soothe yourself, you are more capable of being there for yourself if you fail (and you will eventually fail or will make mistakes, because nobody is perfect 100% of the time). This means you will be able to handle disappointment without spiraling into self-criticism and self-attacking or shame. You will be able to meet yourself wherever you are (emotionally and at whatever your skill level) and you will be able to understand, support, nurture, and encourage yourself to learn from your mistakes and get back out there and try again (if that is important to you). By relating to yourself in this way, you are not motivated by fear or your Threat System. In fact, you may even be more comfortable with yourself which means that you can do a better job. Activating your Soothing System makes you more resilient in the face of life setbacks. Soothing is a source of strength, not a vulnerability.

However, unfortunately, for many people, the Soothing System is often both hugely misunderstood and underutilized, or it is completely blocked. This is particularly true for individuals with difficult family upbringings such as attachment wounds, or with a history of complex trauma. For example, due to our developmental histories, or painful emotional or interpersonal experiences (such as childhood experiences of shame, rejection, bullying, parental hostility or parental unresponsiveness), the very behaviours and emotions that associated with caring or safeness (warmth, closeness, and soothing) can unfortunately inadvertently trigger a sense of Threat – not safeness!

Interested readers are encouraged to read more about this in the following articles:

- How Your Attachment Style Affects Your Emotion Regulation & Your Relationships

- Understanding Your Window of Tolerance

- Adverse Childhood Events (ACEs)

As previously discussed, an imbalance in these three Systems can lead to mental health problems. And we know that individuals who underutilize their Soothing System often also experience intense shame and self-criticism which triggers an excess of cortisol and stress hormones and this (for example) can result in hostility, suspicion or defensiveness, which can greatly interfere with their relationship with both themselves and others.

Luckily, being able to tap into the Soothing System involves an established set of skills. Thankfully, Soothing skills (see below) can be learned and this fact is backed by extensive scientific research. If you believe that you are over utilizing your Threat or Drive systems or if you would like to learn more about how you can tap into your Soothing System – I recommend working with a Clinical Psychologist who is trained in Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT).

What is CFT?

Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT) was developed to help those with mental health issues that are maintained by feelings of shame or self-criticism. CFT is based on evolutionary psychology and the latest neuroscience of emotions. It teaches practical skills to help people bring balance to the brain’s three emotional systems so they can self-soothe and deal with difficult emotions such as Anger, Shame, Anxiety, Fear, Depression, and Self-Criticism. A major component of CFT is to work with the Fears, Blocks, & Resistances (FBRs) to working with the Soothing System. These FBRs are essentially viewed as being outdated (but understandable) protective strategies that were once helpful (but which are no longer helpful because their consequences now play out in very complex and undesirable ways). These FBRs are all completely understandable once the impacts of one’s developmental history and one’s early learning about positive emotions such as Soothing are considered.

Further Resources:

- Your Brain’s Threat System

- Understanding Your Window of Tolerance

- How Your Attachment Style Affects Your Emotion Regulation & Your Relationships

- The Physiology of Self-Criticism

- Fears, Blocks & Resistances (FBRs) to Self-Compassion

- Common obstacles in learning Mindfulness

- Calm yourself quickly with Soothing Rhythm Breathing

- A list of all articles I have written